Data-driven healthcare: integration

This post is from a talk I gave at the inaugural Digital Health and Care Conference at the Principality Stadium in Cardiff, Wales on the 19th October 2017

I am going to talk about being data-driven in healthcare - how we need to create an architecture that enables us to capture and use data to improve patient care and our clinical services.

I want us to develop an open platform for healthcare in Wales built on a foundation of standards and interoperability.

You need to remember three things, the three “P”s - platform, patient and preparation.

By “platform”, I mean a collection of interoperating computing services built using industry standards a) on which we can build multiple applications for clinicians, patients and managers and b) provides a single consistent and logical patient record.

By “patient”, I mean that we need to re-focus our work on our patients : and avoid simply digitising our old ways of working but instead make use of digital tools to support all citizens to interact with and contribute to their records and importantly, help them manage their own healthcare.

And finally, by “preparation”, I mean that we need to create systems now that support solving our current problems but does not limit future development and innovation. We need to develop an infrastructure that fosters innovation in a safe way.

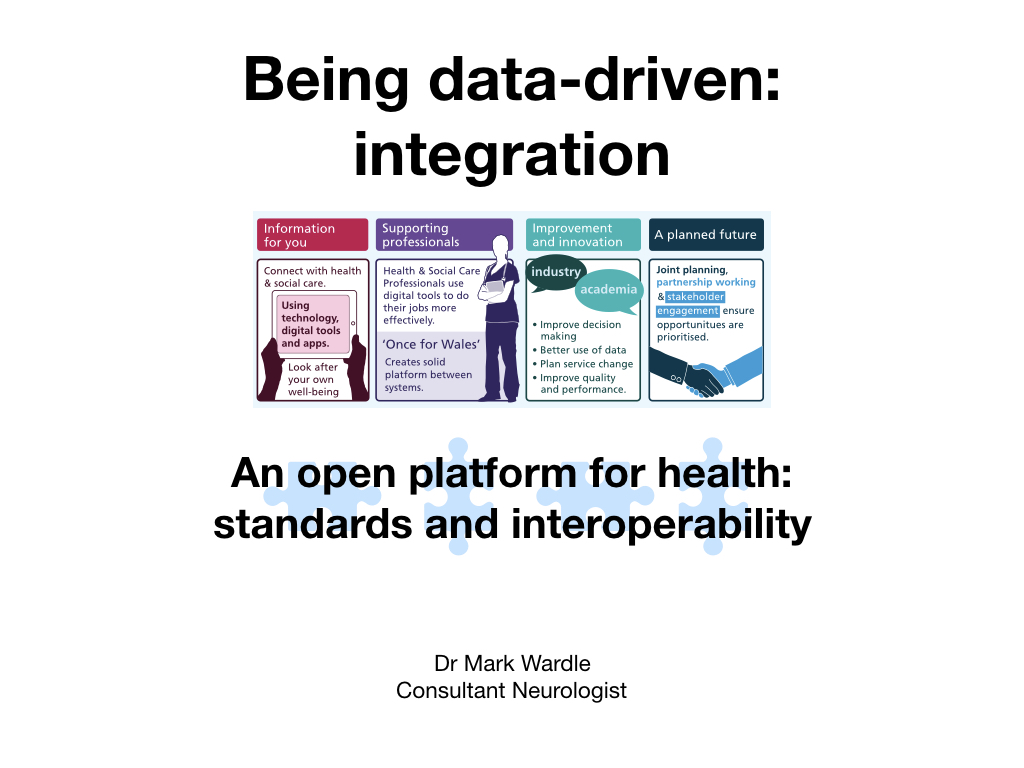

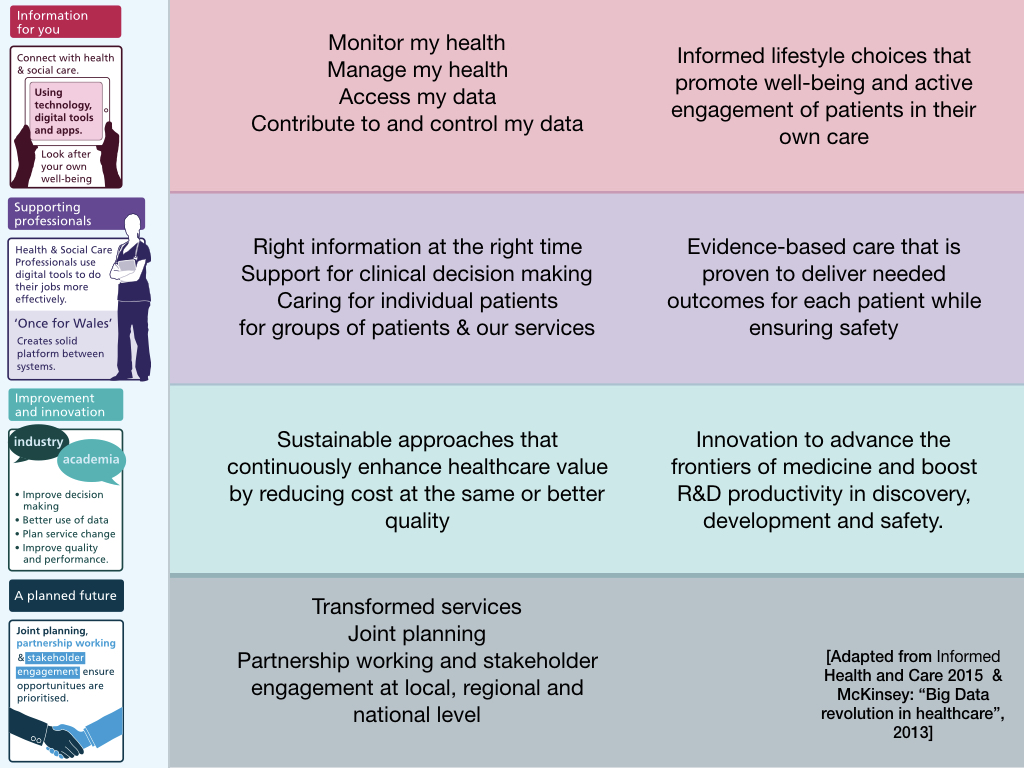

The Informed Health and Care strategy, as you all know, is split into four key themes, focused on the patient, the professional, our services and our future.

Essentially for patients, the requirements boil down to enabling patients to monitor and manage their own health, accessing, contributing to and controlling their own data. This patient focus is important and is essentially a disruptive influence on how our clinical services should develop in the future.

For professionals, we essentially want access to the right information at the right time, information that reduces uncertainty about the decisions we make.

Likewise, we are responsible for multiple cohorts of patients across our clinical services and need to ensure that we configure those services appropriately and permit innovation in service design and research and development.

Similarly, we need to build systems - and I use that word in as loose fashion as possible - that support working in partnership - in collaboration to drive up quality and performance.

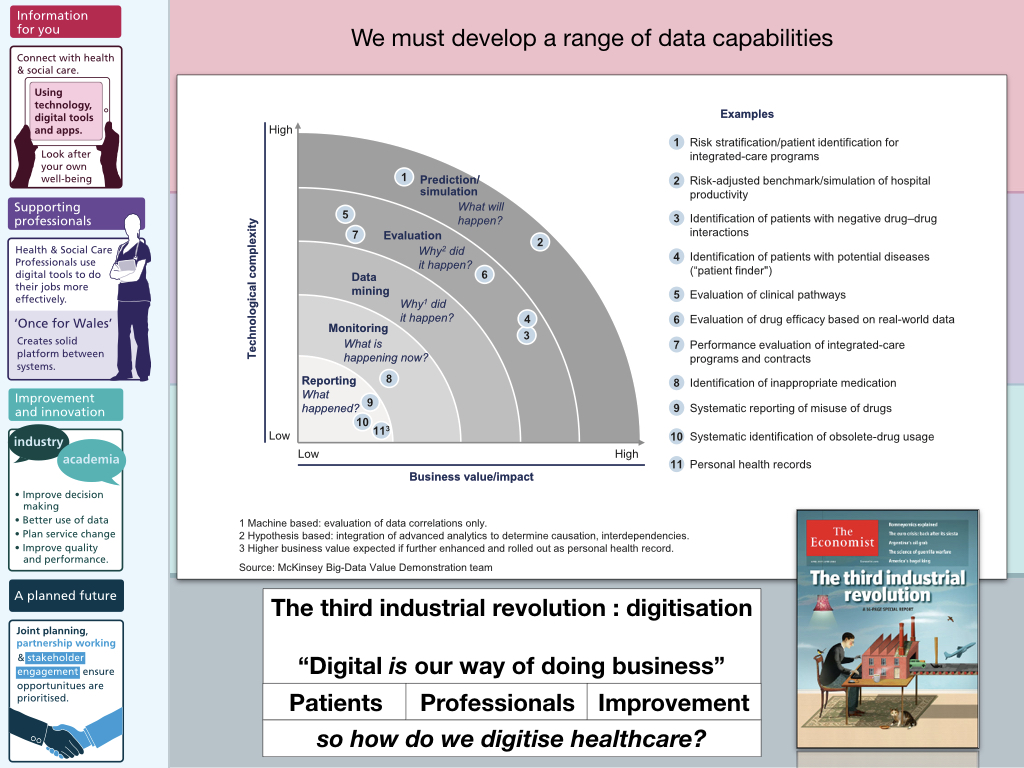

I would argue that the solution to these requirements is not to jump to developing multiple software applications but instead to develop a widespread recognition that DATA is at the heart of those aims.

It is DATA that tells us:

- what happened,

- what is happening now

- why it happened and even, if we get it right…

- and what will happen…

It is DATA that drives our work and digitisation of that data - historically on paper - means that we can do it at scale and in real-time - it is analysis of renal function blood tests that should prompt a real-time notification that our patient is deteriorating.

So the question is how to successfully digitise healthcare?

I spend a lot of time thinking about what “the medical record” actually means and I can’t express it better than the late Larry Weed, the founder of the problem-based medical record, who said, in his Internal medicine grand rounds:

“You’re a victim of it or a triumph because of it. The human mind simply cannot carry all the information without error so the record becomes part of your practice”

And of course by medical record, I am not talking about an application running on a desktop computer, on an app on a mobile device: I’m talking about the logical medical record comprising all of the information that supports our decision making. It’s the data - the medical record that counts, and not the applications that we use to access that record.

Joined-up thinking

I think our biggest failure in healthcare IT is to create artificial boundaries between data : for example, in 2001, The Bristol Heart Enquiry highlighted the consequences of separating administrative and clinical data.

“The various clinical systems, many of them paper based, differed from one another and had no relationship with the administrative hospital-wide systems. The funding made available in the late 1980s and early 1990s for medical and later clinical audit helped to reinforce this separation by making available to groups of clinicians money for small local computer systems. The lack of any connection between these different systems, one administrative, the others clinical, for collecting data cannot be explained solely on the basis of some technical or technological reason. It was just as strongly a reflection of a mindset that clinical matters were the sole domain of clinicians and non-clinical matters, to do with the management of resources and with the movement of patients into and through the hospital, were the preserve of managers and administrators.”

We must stop thinking about administrative systems, clinical systems and research systems, and instead, focus on data - on the patient and the varying types of longitudinal data that are collected - by the patient, their devices and the professionals involved in their care. Of course, different people have need to see those data in different ways - different perspectives - different prisms, but the data - the patient record - that is key.

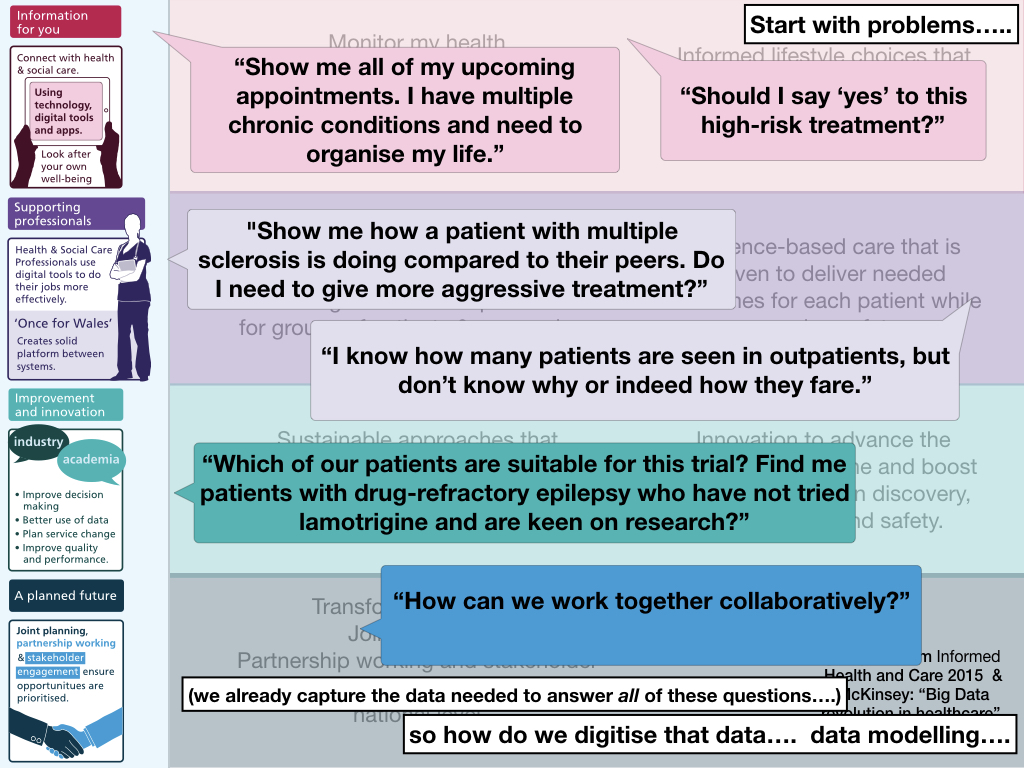

Start with problems

So I recommend starting with PROBLEMS.

Problems define your requirements.

For example:

- “Show me all of my upcoming appointments. I have multiple chronic conditions and need to organise my life.”

- “Should I say ‘yes’ to this high risk treatment?”

- “Show me how a patient with multiple sclerosis is doing compared to their peers. Do I need to give more aggressive treatment?”

- “I know how many patients are seen in outpatients, but I don’t know why or indeed, how they fare.”

- “Which of our patients are suitable for this trial? Find me patients with drug-refractory epilepsy who have not tried lamotrigine and are keen on research?”

- “How can we work together collaboratively?”

For instance, what are the informatics challenges facing us in solving “show me all of my upcoming appointments”, particularly if we need to solve that across multiple organisations? We need to integrate data from across multiple PAS - and provide a unified view.

We should prioritise our requirements and consider the data requirements.

So how can we help patients come to decisions about a high-risk treatment? How can we understand our outpatient services without setting in motion systems to track clinical problems and diagnoses in a structured way rather than free text?

How can we make Wales the best place for IT, for collaboration?

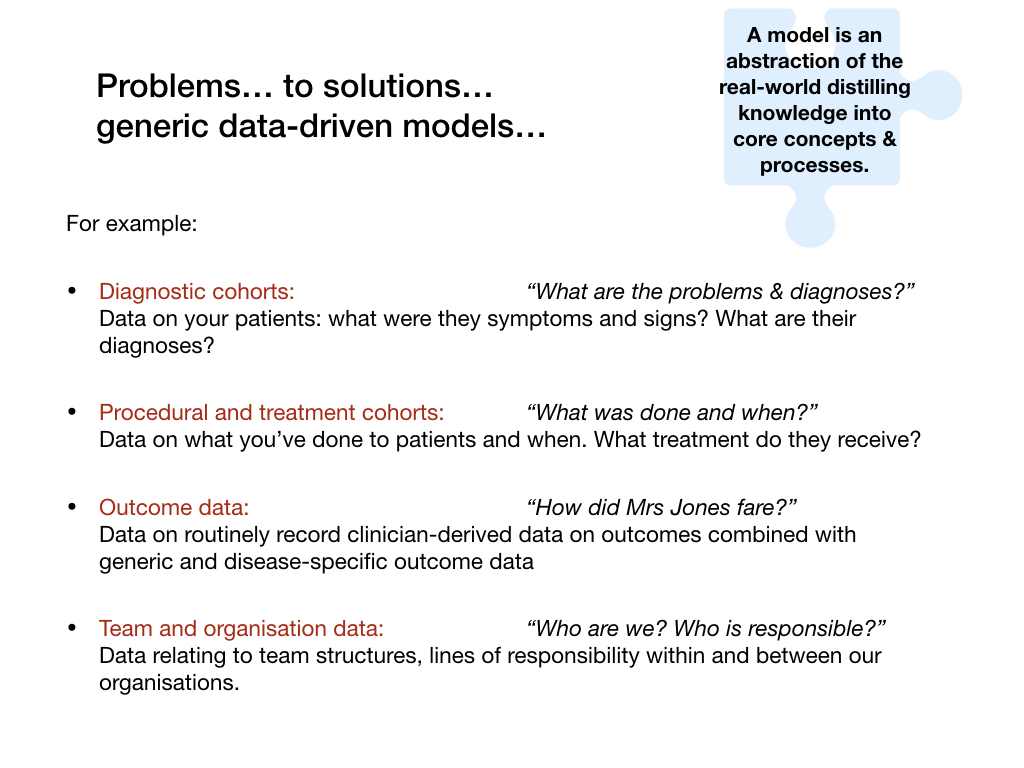

My thesis is: we think about the data required to solve those problems.

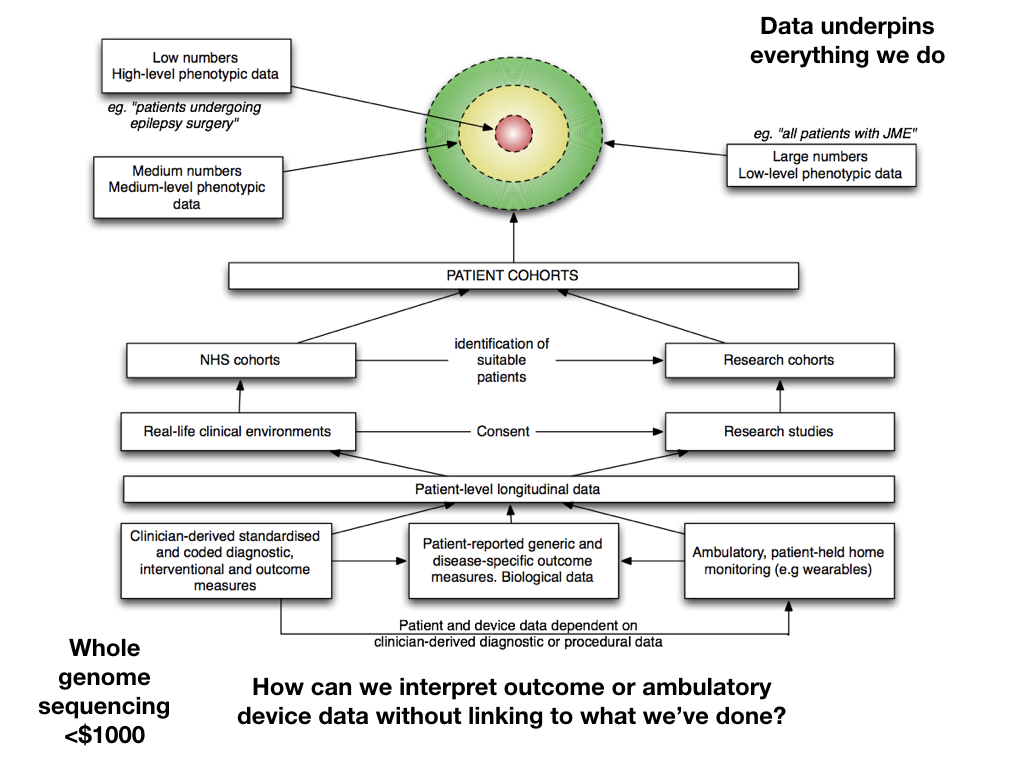

So given our problems, what kinds of data must we capture and link together to make them meaningful? I feel strongly that understanding cohorts of patients - grouped by disease or clinical problem or intervention or contact with a specific service - these underpin the interpretation of all other data. For example, how can we interpret patient reported outcomes without understanding all of those issues? Information has to be linked.

And so essentially, we stop thinking about applications and think instead about the patient record, combining administrative, clinical records - including GP and hospital records, laboratory and other sources of information - into a logical longitudinal record.

And when we start thinking about a patient record, we must consider how we link disparate pieces of information together to solve our problems. We must stop creating data silos with information unusable outside of where it is collected.

Here is an abstraction of a logical longitudinal record:

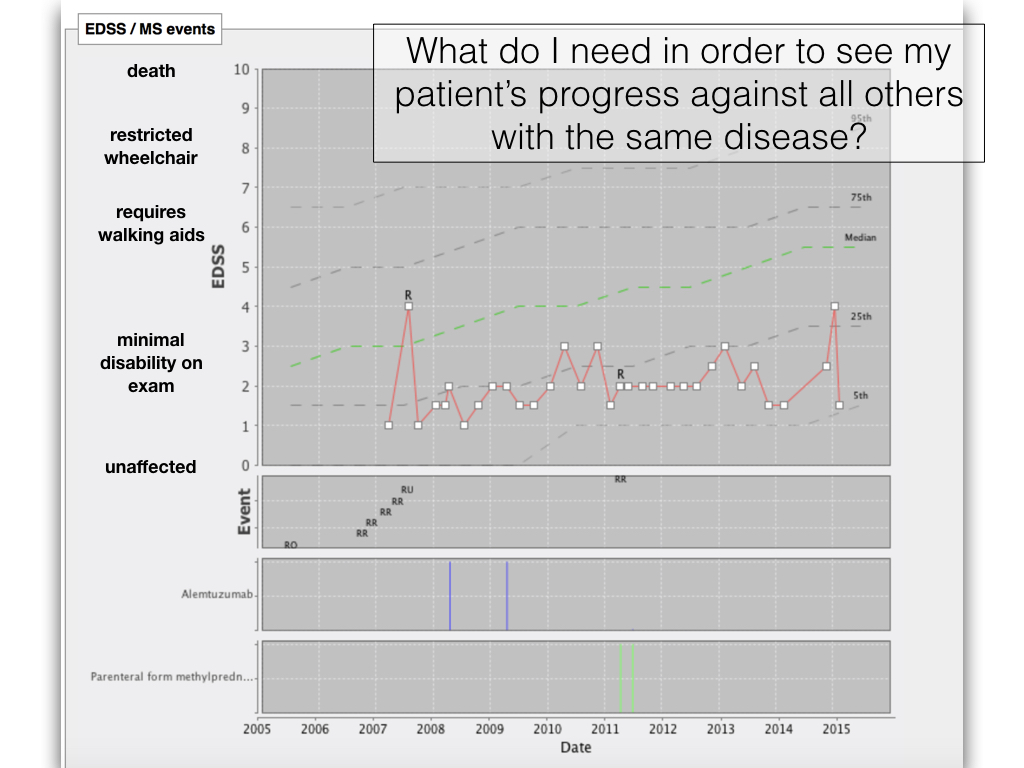

Perhaps an example would be useful. Here is a screenshot from my own clinical information system that is currently used to look after over 25,000 patients in Wales and records 4,500 clinical encounters every month for a range of neurological and non-neurological diseases:

This chart shows the progress of a single patient marked with a red line against the progression of the disease in all patients with multiple sclerosis in South East Wales.

How did we do this? The chart is generated in real-time using analysis of all patient data taking to into account diagnosis and disease progression recorded by patients and clinicians. In clinic we find it useful to also see charted the medications received by the patient - you can see that they have had alemtuzumab and methylprednisolone and also their exacerbations in their disease - marked with an “R” - for relapse.

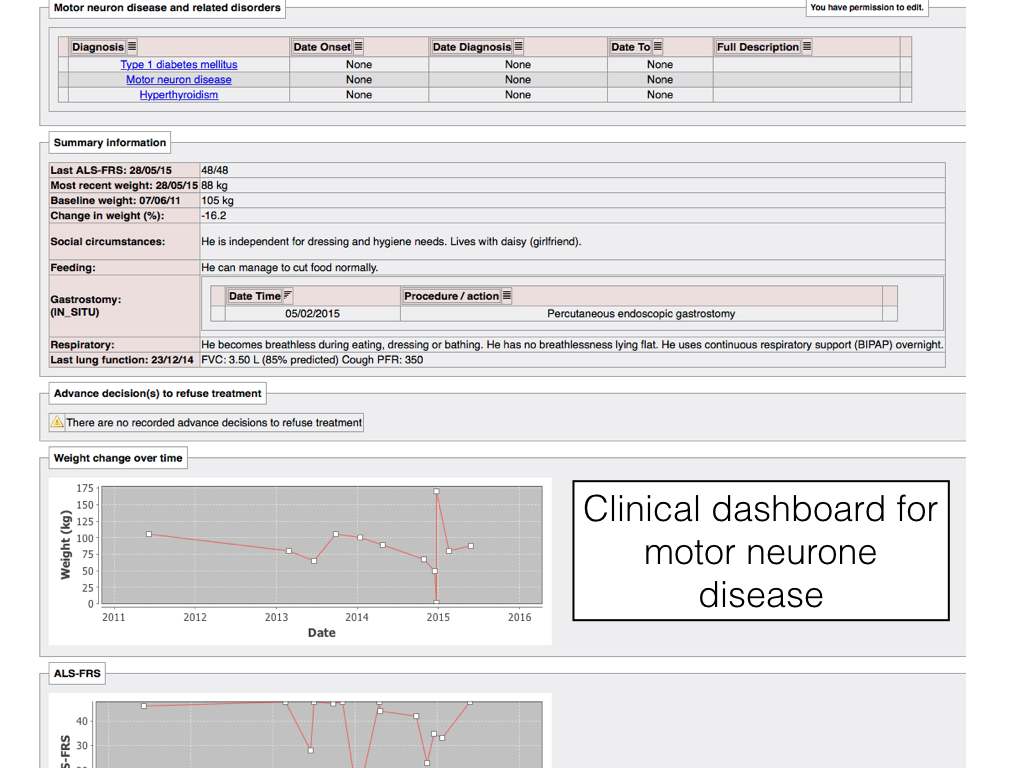

We now have years of longitudinal data for a wide range of cohorts of patients such as multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and Parkinson’s disease and real-time analytics and clinically-useful dashboards form an important part of making it worth entering information. It is no good having either professionals or patients enter data or use devices to collect data unless we use that data for decisions.

SNOMED-CT

One of the most important aspects of our work must be to support the collection of data by clinicians for clinicians in the day-to-day work. One important technology is SNOMED-CT a comprehensive terminology that supports the entry of structured clinical information coded in a computer-readable format. This is a KEY enabler of data-driven clinical systems and analytics. Using this, we can record a patient has multiple sclerosis and firstly expect that other software will understand this diagnosis and secondly understand what type of disease that this is. SNOMED-CT is an ontology - it not only includes concepts but the relationships between them, so I can potentially find all patients with a demyelinating disease and it will support me finding patients with multiple sclerosis but also related conditions.

Entering codes can be as simple as typing free text.

With such a data-driven foundation, it becomes straightforward to build useful dashboards that take data from multiple systems and multiple sources and presents them in a useful fashion for end-users. Here we have a dashboard bringing together important information about a patient with motor neurone disease:

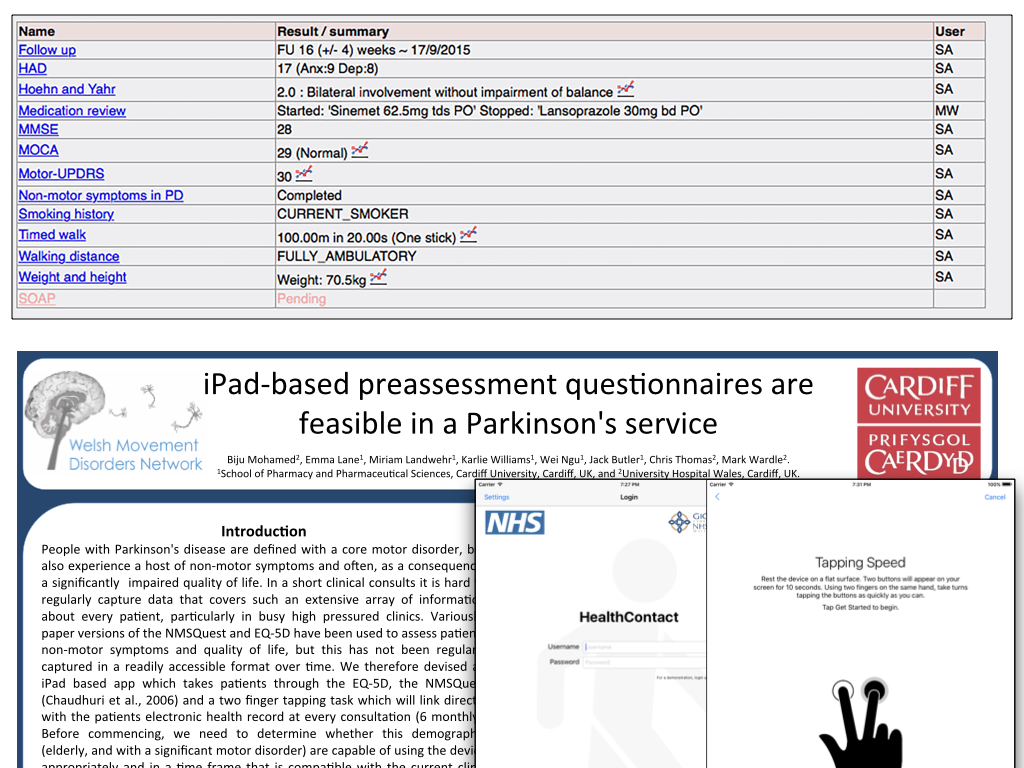

And we must ensure our patients can engage fully…. in the Parkinson’s disease clinic we have successfully trialled the use of iPads to connect to the EPR and allow them to contribute to their medical record via adaptive questionnaires. Here is a view of all patient data from a single clinic visit that is used to generate our clinic letter automatically. Each of these outcomes can be graphed to show changes over time.

Scaling

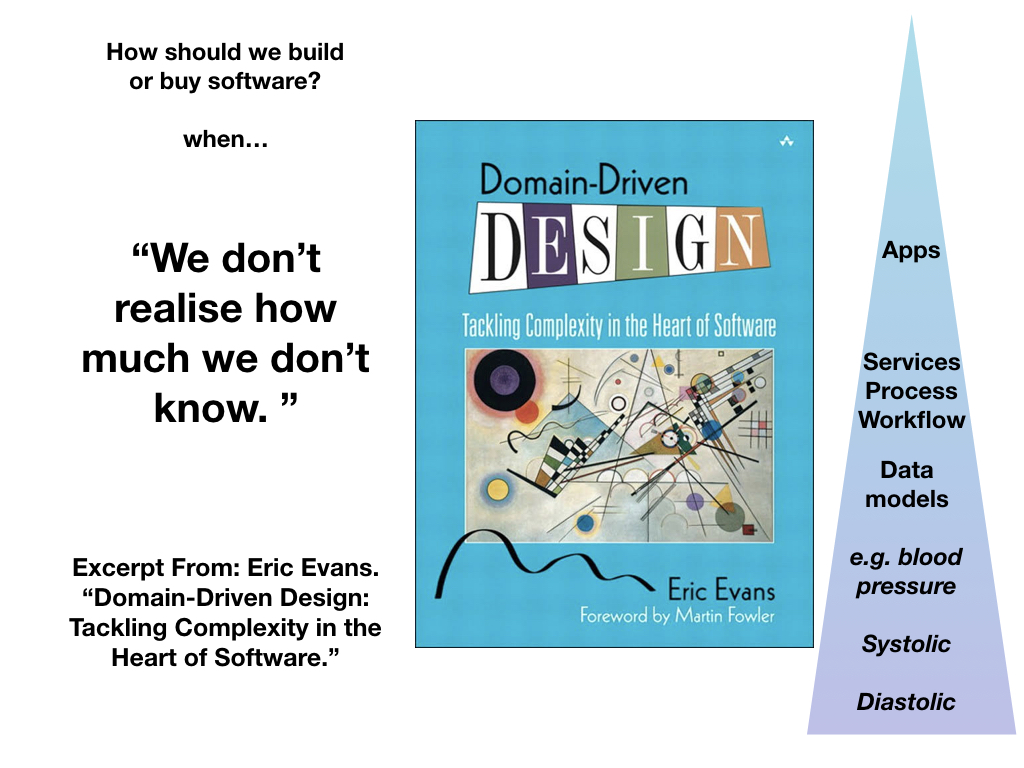

So how can we take what we’ve done and scale it to every other clinical encounter in Wales? The problem is that “We don’t realise how much we don’t know”. I am sure that there are some clever people who can take my Parkinson’s disease medication and disease progression data and turn it into something even more useful, who can then link it to home monitoring technology and falls detection and send our team alerts when necessary.

How can we design or implement software that solves our problems today and adopts a sufficiently flexible approach that we can innovate and adapt to solve the problems of our future?

If you haven’t read it, I recommend Domain-driven design by Eric Evans - a focus on data modelling to support complex systems.

We start with a model of our data; this model will change but slowly over time — a blood pressure measured in the right arm will always be a blood pressure measured in the right arm. On top of this information model, we build conceptual models of workflow and process, a platform made up of core services providing access to those models and finally lightweight applications. Process and workflow models will change much more frequently that our data model and likely need dynamic customisation via rules engines for different contexts. Applications should be the most ephemeral component of our designs.

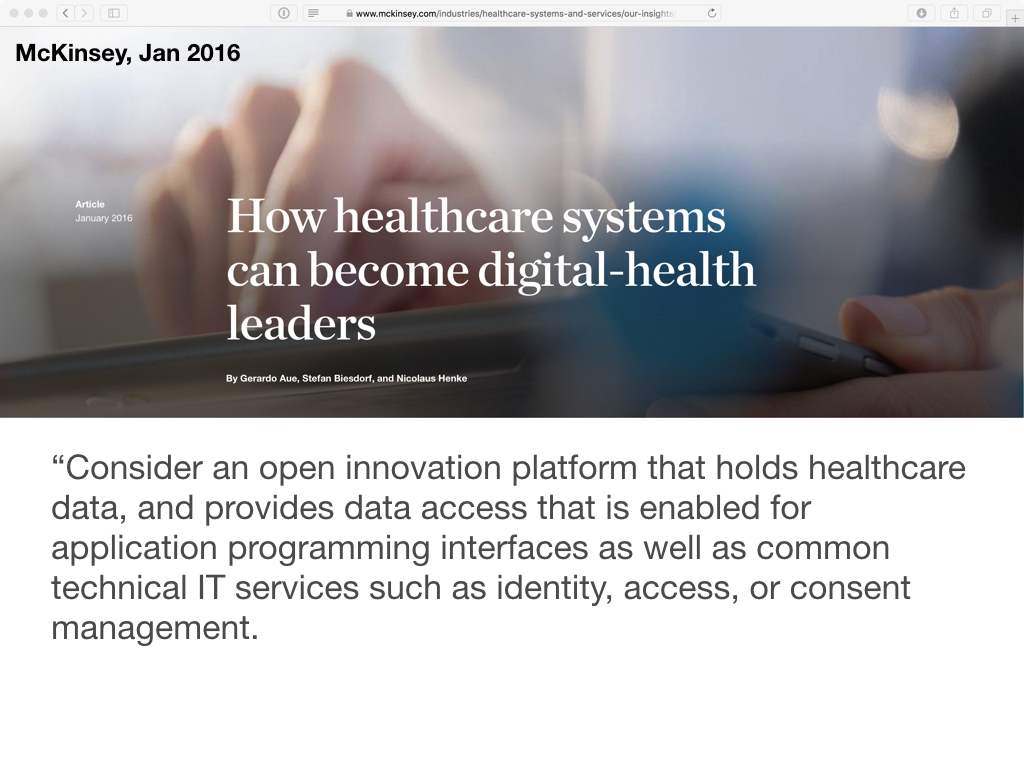

An open innovation platform

As a result, we create an open innovation platform built on a secure foundation of structured, semantically meaningful data. We provide a range of core application programming interfaces or APIs - providing access to a range of useful services such as identity, access and consent. Together, these form a platform.

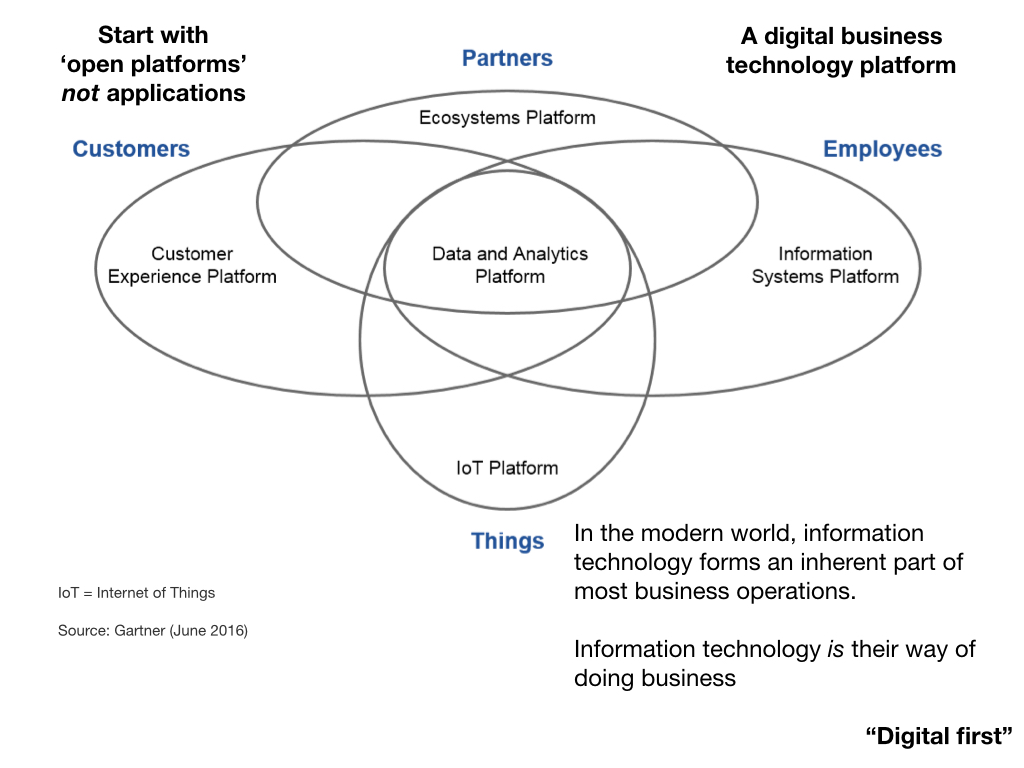

We must stop thinking about applications and instead think about how our platform can interact with our work streams - our patients, our professionals, our partners and the future.

Most businesses have already realised that information technology forms an inherent part of their operations; in essence, they have realised IT IS their way of doing business. It is about time healthcare did the same.

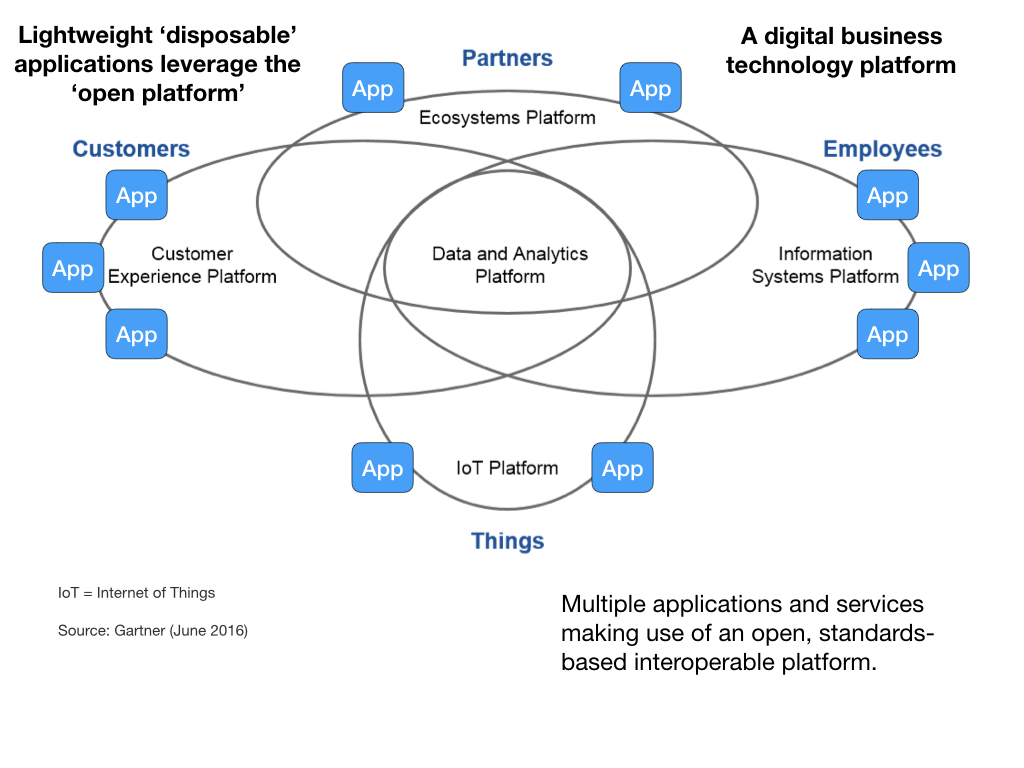

So the model becomes a data-centric core, open platforms exposing those data and multiple lightweight applications solving specific process and workflow problems for patients and professionals.

As a result, we create a single patient record : and ensure that we can see all of the relevant information for a patient while not getting lost in an excess of data.

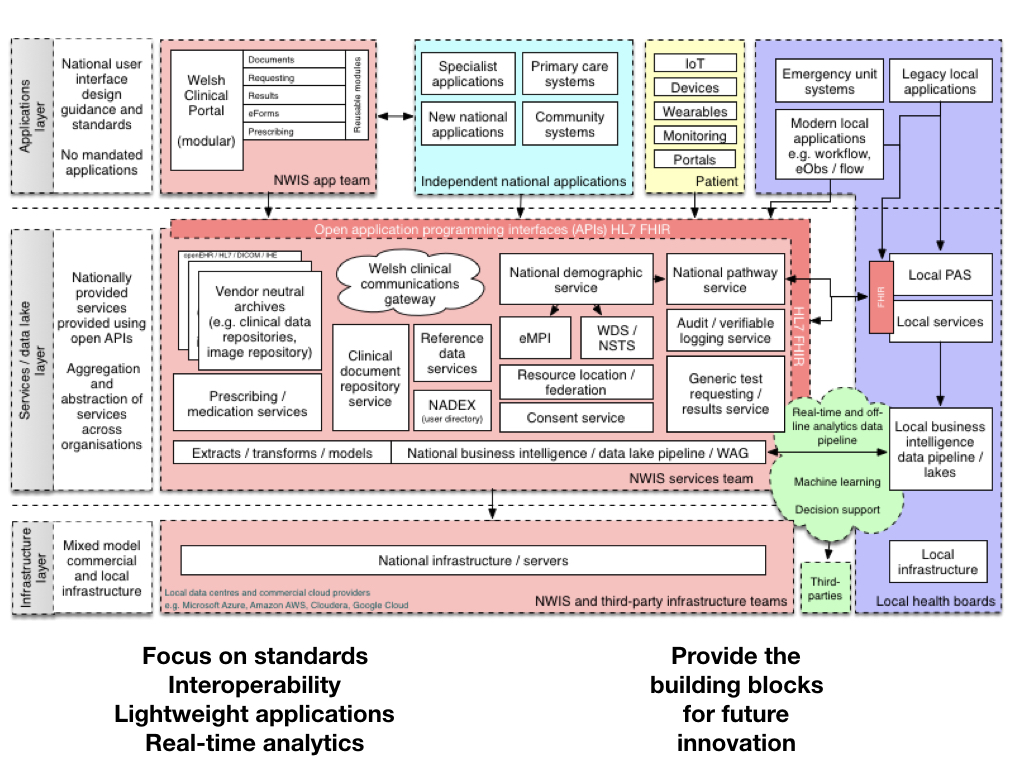

And this is how it could look in Wales:

We open up our core services, create a platform leveraging new technologies such as HL7 FHIR to expose application programming interfaces that can be used by multiple applications providing different views and different perspectives on a single patient record or collections of those records.

[ explain diagram ]

We must focus on data standards and interoperability, creating lightweight applications at pace and design useful real-time analytics services for clinicians and managers. Critically, we build a platform that can provide the building blocks for future innovation.

Summary

So in summary, I remind you to remember three “P”s : we need to build an open platform, ensure we focus on our patients and… prepare for and permit future innovation by understanding that we don’t have all of the answers… at least - not yet.

Thank you.

Mark