What would I do for healthcare if I were Google?

Google was created in 1998 with a mission statement:

“to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”.

I remember using Gopher for hypertext then switching to using the Mosaic web browser on Athena workstations on starting University in 1993, and then searching the web using Altavista in 1995. When Google was launched, most early internet users quickly switched for its fast and accurate search.

Google has diversified since those halcyon days and the establishment of Alphabet as its parent company reflects this diversification into areas of technology such as self-driving cars, mobile devices including the Android platform, and even drone delivery.

I understand that the original mission statement is under review and that is understandable when one considers the range and breadth of Alphabet’s interests.

However, I think the mission statement is exactly right for healthcare and we need to, as a health community, emphasise the importance of making the right information available to clinical professionals and our patients at the right time.

Google Deepmind

I am particularly interested in the current Deepmind push into healthcare. Indeed, Deepmind Health has announced collaborations with the Royal Free Hospital for the automatic computer-aided identification of acute kidney injury and with Moorfields Eye Hospital to use machine learning to automate the analysis of optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans.

The application Streams is an important push to deploy applications running on mobile devices within the NHS. I think this is the most important result of their work; the fact that it is screening for acute kidney injury is simply a good choice of proof-of-concept. The greatest benefit is proving that a mixed economy of mobile applications that interoperate using data standards and standard application programming interfaces is not only possible but provides important advantages over the usual monolithic application architecture that is usually employed within a single organisation.

It is therefore logical that Deepmind Health should adopt, with vigour, the original mantra of Google at its own conception; to paraphrase:

To organise healthcare and patient information and make it universally accessible and useful.

When I see a patient…

As I quote in my clinical design document from the legendary Larry Weed, in relation to the medical record:

“You’re a victim of it or a triumph because of it. The human mind simply cannot carry all the information without error so the record becomes part of your practice.” Dr Larry Weed, Internal Medicine Grand Rounds, 1971

I have an abstract view of the “medical record”. To me, a medical record is all of the information pertaining to a patient that is useful in looking after the patient. At the moment, most clinicians use a myriad of different sources of information: the patient him or herself, carers and relatives, paper records as well as electronic systems. Early computerisation of laboratory and radiology systems means that most clinicians use electronic systems for these types of results, but most use paper for the narrative record.

In my own organisation, we have a range of systems, one of which I designed and built myself: the PatientCare suite of applications. In addition, we have access to a “digital health record” which is used to scan in paper records and make these available in a relatively unstructured way in an online browser. While this solves problems for medical records departments and allows a view of the record from multiple locations without having to track the notes, those data are not usable in any reasonable way: they are scanned documents.

An important conclusion is that clinicians are faced with an information overload of unstructured information and few tools on hand to make sense of that information for a patient, or indeed group of patients, under their care.

Supporting clinicians with intelligent computing

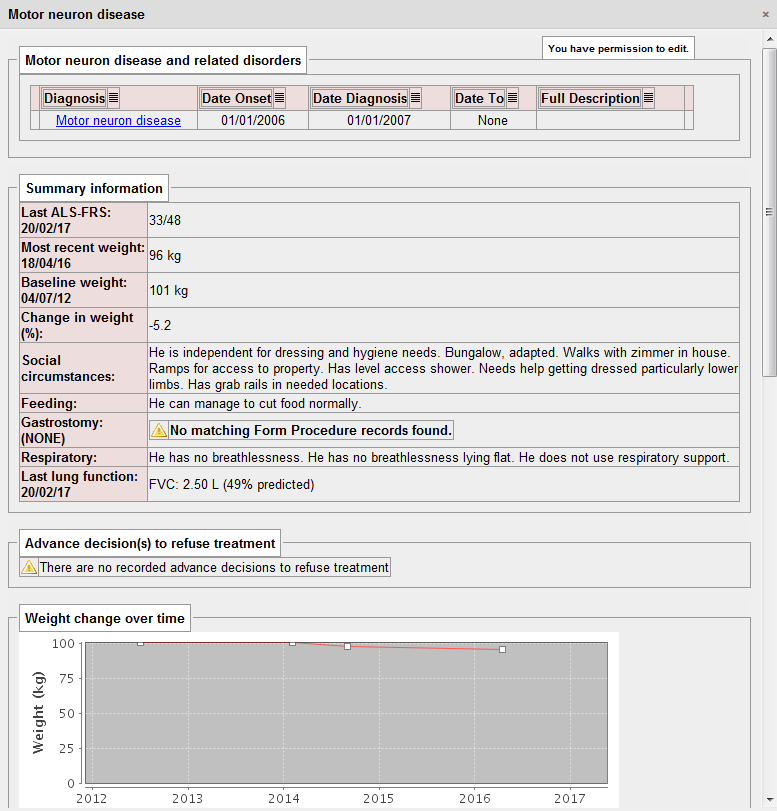

For a patient with motor neurone disease, I need to know several important pieces of information, including an indication of the severity of their disease, social circumstances, issues relating to feeding and weight, gastrostomy insertion and complications as well as their respiratory function. The key is that all of these pieces of information help me to help the patient at that point in time. It is no surprise that I extract all of this information in a disease-specific dashboard as part of my PatientCare electronic patient record:

Importantly, this information is extracted from a range of locations within the electronic record. The use of SNOMED CT means that computationally, we can simply ask “does this patient have a gastrostomy?”. In the logic to determine this, we look for procedures for the insertion and removal of gastrostomy and can therefore determine whether a gastrostomy is in-situ at any given time point. It doesn’t matter whether the gastrostomy is placed via a percutaneous endoscopic procedure (PEG), a radiologically-inserted gastrostomy (RIG) or even a surgical gastrostomy, because we can use the structures within SNOMED CT to make logical inferences about a type of procedure irrespective of how it is recorded.

Intelligent computing can work effectively if there is a coded and structured medical record. Historically, healthcare computing has been about supporting the administration of healthcare facilities and not supporting healthcare. The natural conclusion is that we need to improve our prospective longitudinal recording of structured information within the healthcare record.

I suspect that the Deepmind Streams project could be much more powerful if it had structured information about medications, changes to medications, procedures and diagnoses at its disposal, and not simply, as I suspect, the raw data from the laboratory about renal function. Indeed, I understand that currently the Streams project is more about proving the idea of integrating a third-party application within the NHS than any use of artificial intelligence at the moment.

Patient data, information governance and confidentiality

I find it easy to justify accessing a patient record. They are normally sitting in front of me at the time - I am their physician and I try to help them as much as I can. This is direct care.

I also manage local services and so use aggregated data in order to ensure my services are working effectively and safely. We frequently anonymise these data for aggregation purposes, but as we’re managing a service, and I’m working for an NHS organisation, there is usually no difficulty in using these data.

Finally, I am involved in research in which patients have explicitly consented for their data to be used as part of one of our observational, epidemiological or interventional studies. With explicit consent, I have no difficulty in using those data, usually anonymised, in the process of scientific research.

Information governance is frequently used as a reason to prevent sharing of information between organisations but this is difficult to justify. The important thing is what patients themselves would think and, whether they think it is reasonable.

Commercial for-profit companies providing or supporting health care are subject to the same information governance rules. However, the media and public view commercial entities with suspicion - what will happen to patient data? In most cases, such suspicion is not justified, but examples such as the furore surrounding the care.data NHS England project demonstrate the issues at hand. A single misstep in either the use of data, the perceived use of data or lack of clarity surrounding either has the potential to close down any programme, however innovative. The debacle with care.data risks future projects to use patient data for the good. The Deepmind Streams project has already received criticism from patient and privacy groups.

What do I want from Google Deepmind?

Artificial intelligence (AI) has amazing potential for taking information from disparate sources and present and analyse data in order to support clinical decision makers improving patient safety and care. Not only can we plan to bring together the right information at the right time, but make logical inferences from those data in order to improve patient care.

We are at an early stage of development and so it is vital that there is a robust framework in which such technologies can be tested and evaluated in a safe way. It is vital that AI is introduced within a quality improvement framework. Controversial deployments of AI such as the IBM Watson - MD Anderson cancer project, which have ended in failure risking public and media support for the introduction of AI into healthcare.

I want the most valuable and useful data accessible to me when I am looking after patients. Google Deepmind should be asking the same question: how can they best obtain those data in order to progress their individual mission: “Solve intelligence, use it to make the world a better place”. The answers are the same:

1. Make more structured data available

We need robust interoperability, a focus on data standards and real-time, clinician led structured data capture. The fantastic interoperability summit on 2-3rd March 2017 demonstrated an enthusiasm and energy from those interested in clinical informatics in the UK.

Build an effective open-source toolchain

However, there are difficulties: a lack of tools for system suppliers, small enterprises and mobile app developers in order to make most effective use of such standards. I have released an open-source SNOMED CT terminology server in order to try to make these tools commodity items; essentially the foundation on which more innovative clinical solutions can be built. We need more. We need disruptive technologies that will lower the barrier for entry for start-ups and innovators into the health application marketplace.

I would argue that we as a community should be working on a complete open-source software stack that can provide core platform functionality including integration with existing systems such as those relating to patient administration, laboratory and radiology. However, at its core are the tools necessary to rapidly and effectively build solutions to create and store structured healthcare data. We need to make the building-blocks of health applications freely available so that innovation can add value to patients and health professionals. For too long, any startup enterprise has had to begin by building the roads on which they will drive, before they can build the vehicles of the future.

Build an interoperability infrastructure

In regions where there is already large existing infrastructure, the platform could be installed as only an integration engine, bringing together information from existing services. As such, developers of user-facing applications and those who wish to support clinical care by using computer algorithms and artificial intelligence, can be used in any organisation in which the integration engine exists. Much like an open-source version of Google’s search appliances for health, we would be able to liberate data from proprietary systems, creating an open health data repository.

I am building a FHIR-based microservice around our hospital PAS presently. The PAS provides a proprietary, non-standard SOAP API for client applications. I’m going to do the same for our regional enterprise master patient index; it simply needs to create a FHIR end-point and wrap a HL7 PDQ call. It is not difficult to do but there are many such systems around, all of which need integration.

Natural language processing

In addition, there is an enormous amount of data held in clinical correspondence. We have need to make this information more accessible; there are already commercial solutions that use natural language processing (NLP) to release structured data from narrative textual descriptions of clinical course and progress. Other divisions within Google have extensive experience of natural language processing, and these tools should be introduced and evaluated to make information accessible and useful. We need to start work on evaluating different technologies from different vendors, commercial and academic, in order to apply NLP in a healthcare arena.

I have seen one commercial solution in action and it is squarely aimed at the identification of patient cohorts for specific research studies, and not for real-time use by clinicians in the day-to-day care of patients.

2. Ensure a robust framework in place to satisfy public perceptions

Importantly, it is not possible to freely liberate health data and make it openly available. Instead, there must be appropriate governance and data flow arrangements.

There are several options. Firstly, Deepmind’s current course takes an organisation-by-organisation approach, starting with small projects and iterating and proving the concepts. This is sensible initially but successful roll-out to other organisations will be slow and tortuous. For each organisation, an organisation must adopt Deepmind as a data controller. I would argue that the resulting infrastructure may be patchy and difficult to integrate, particularly when trying to work across organisations.

The second is to focus on explicitly consenting adults and create relationships with academic researchers, many of whom have large cohorts of well-phenotyped patients with outcome measures and highly-structured data. We have detailed longitudinal data on our patients with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and motor neurone disease for example. There are parallels with the academic open data movement in which researchers share their data, code and methods with others in order to support reproducible research.

The third approach is to put the patient at the centre of the strategy. Apple’s ResearchKit has provided an open-source framework that makes it trivial to have patients sign-up and consent to research and complete patient-reported outcome measures. This is however, only a small piece of the jigsaw but it does conceptually mark a shift from targeting applications at health professionals to putting the patient at the centre.

Apple’s ResearchKit does not solve where the resulting data is stored or how to make the most effective use of such data in a busy clinical environment or indeed, avoid the creation of multiple data silos. In addition, that framework is bound to the Apple device ecosystem, and my own experience has shown that we need a multimodal approach to data capture for patients: young patients with epilepsy may use their own devices but an elderly cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease benefitted from supervised use of a shared tablet device actually in the outpatient clinic in our study. No framework should require devices from only a single vendor.

Distributed patient control

As such, I would make a push for creating a distributed system to give individual patients control. In this, we design a framework in which patients control an account for recording explicit consent and logging health record access. This account provides pseudonymous data-linkage services so that one service cannot necessarily find out to what other services the patient is registered.

For example, in the United Kingdom, all patients have an NHS number. When a patient attends a healthcare organisation in the UK, that organisation can independently generate a pseudonym based on a mathematical hash of the NHS number and their organisation- or service-specific salt and register for access against the patient’s own consent account. For NHS organisations, a record access log entry can be made using this unique identifier. For research projects, the log entry records the request which can be subsequently shown to the patient with information about the project encrypted using the patient’s own private key: explicit consent results in the recording of that consent in the ledger. The ledger then becomes a distributed transactional record of record access and consent. Before a research project accesses a record, it can make a request using the known patient data, generating its own hash of those data, and makes a request to the distributed consent ledger.

As I write (9/3/17), Deepmind have announced work on a verifiable audit log in order to safely log the access and use of data, computing incremental hashes of the data as it is added so that it is possible to demonstrate, without doubt, that the data has not been changed at a later date point. It uses a nested tree design called Merkle trees but this is simply an optimisation to limit the computational requirements whenever data is added. Presently, I understand that this is designed to be a centralised record. Such centralisation means that potentially, whoever controls the ledger can change the ledger, simply by re-computing the hashes of the data to reflect the change. Computationally, this may be inefficient, but the verifiable log only becomes verifiable when the ledger is held by a trusted party. For the Deepmind collaboration, I would imagine the NHS organisation holds the ledger while Google writes to it. As such, the organisation can vouch that no log has been changed or deleted inappropriately.

One key advantage of Merkle trees is in the ability to support the synchronisation of data by allowing the rapid identification of which data has been synchronised across a distributed system and which has not. Indeed, this approach is used in distributed databases such as Apache Cassandra to do just that.

I would therefore suggest that we as an interoperability community work towards developing an open-source distributed consent and log framework which is held securely by multiple trusted health organisations. By distributing and synchronising such data among multiple trusted parties, one can offer guarantees that no single organisation can make a change without it being identified by all other organisations, or indeed by the patient or their proxy. A holder of the ledger, and there could be many, cannot themselves re-identify the patients within as a result of the use of multiple service-specific pseudonymous identifiers.

Update 21st March 2017: Additional information relating to Merkle trees in this blog post is available on a more recent post.

A worked example

A public and private key is generated for the patient at registration. This private key is used to encrypt information within the patient’s ledger but is itself encrypted using the patient’s password. If the patient changes their access password, then only the private key need be re-encrypted with the new password.

The summary care record is generated from the general practitioner’s record - these data, including core diagnoses and medications are recorded against a unique identifier computed as a hash of the NHS number, the year of birth and a salt unique to the national summary care record service for that patient : a service-specific salt. Within a distributed ledger, the description of this service, the core data and a link to an end-point service providing more data is encrypted using the patient’s public key. As such, using one of potentially many third-party services, a patient could login to their account, access the information in their ledger and importantly, see who has accessed their record and choose those organisations or services who may see their record. An organisation holding the ledger cannot identify the patients within, or indeed, determine to which services or research projects any logs relate. Individual services who can generate a pseudonym using the appropriate recipe can consult the ledger, write to that ledger and determine patient consent.

3. Encourage a mixed-economy of healthcare applications.

NHS organisations that tend to procure large-scale enterprise-wide clinical information systems such as Cerner’s Millennium platform or Epic limiting the scope for innovation and small to medium enterprises to interoperate and add value. The current environment within the NHS for small and medium sized enterprises is difficult. There are many procurement rules and even when an enterprise can sell to customers, deployment within the NHS is difficult. Hosting services within the NHS N3 are expensive and integrating with existing systems difficult. My final request for Google Deepmind, is to make the case for small, well-defined applications that interoperate with the wider data economy. Proving the effectiveness of this approach is difficult for those of us trying to create those applications.

Junior doctors use WhatsApp on their own devices for communication within their teams in order to manage their workload. Why is it so difficult to contemplate creating a medical application that can provide similar functionality, but ensure that patient-relating communication is recorded against the patient’s record? We need to encourage and foster innovation within NHS information technology.

Final thoughts

Of course, this isn’t really a manifesto only aimed at Google, although I think their priorities converge with ours in the interoperability community and ultimately with those for whom this is most important: patients. However, while there is considerable momentum behind open standards and interoperability, we need considerable backing from a range of disrupting influences to transform the healthcare information technology landscape. We also need to lower the barrier for entry for new startups and allow innovation to flourish, while maintaining information governance.