Disruptive influences in healthcare: the future

I previously discussed three disruptive influences in healthcare in my previous blog post that, over the next five years, will disrupt both the provision of healthcare and the technological solutions currently used to support that care:

- Changes in the models of care

- Patients as active participants

- ‘Hospitals without walls’

And subsequently, I tried to give an overview of how current strategies used by health services and commercial companies will struggle to meet those disruptions, principally as a result of a focus on single organisations and enterprises.

I hope to draw these strands together in one place and hopefully provide some important context for some of my other blog posts. In my view, the two planks of work to form the foundation of our work are:

- An “open decentralised platform” for healthcare made up of multiple standards-based interoperable services and data repositories.

- A single distributed logical patient record made up of multiple shards connected with multiple pseudo-identities wrapped in a consent model.

In essence, we need the right structures in place to allow us “to organise healthcare and patient information and make it universally accessible and useful.” We need to be much more ambitious and yet plan to iterate to get to that future.

1. Open platforms in health

Fundamentally, administrative and clinical information relating to patients must be made more widely available outside of closed networks and across disciplines, services, organisations and sectors.

To do this, we must discuss the “open platform” approach.

The Internet is one example of an “open platform”, in which open standards result in an open network in which many different software applications and devices can be connected and exchange information. One important consequence of an “open platform” is its use for applications not originally considered by its designers. For example, TCP/IP, the networking protocol that underpins the Internet handles, in a generic way, the low-level handling of bundles of data (messages) between computer systems. This open technical architecture was used as the foundation of the HTTP protocol, although other protocols such as Gopher were also built using TCP/IP as a foundation. This is an example of a layered architecture in which an open platform, the “Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model” is made up of multiple layers in which scope and function are well defined. Importantly, each subsequent layer usually provides a higher-level of abstraction from the detail. Low-levels of the OSI platform handle the physical connectivity and nitty-gritty details of networking such as data exchange and acknowledgements of transfer. Higher-levels allow software to ignore these low levels of networking management and simply exchange information.

The Internet has made information of all types universally accessible, useful and searchable and most of us now do this on mobile devices we carry with us all of the time. We now carry around practically unlimited computing resources in our pockets, so why can we not do that in healthcare?

Why an open platform?

Why does the “open platform” matter in healthcare? I have touched on the problems previously. Essentially, healthcare informatics has been dominated by:

- a focus on administrative functionality rather than prioritising clinical care and the patient.

- large commercial vendors with closed systems and little or no interoperability.

- a focus on the procurement of “products” based on features on a capital expenditure basis with old-fashioned project plans built using a waterfall methodology with start and completion dates and little or no concept of iterative improvement

- organisations that are hierarchical and autocratic, designed to funnel information upwards and decisions made by those at the top flowing downwards. In essence, such structures have arisen as a result of trying to manage risk; when one considers large multi-million pound procurements, one must attempt to slow down decision making and reduce the risk of a bad decision

- organisations that are risk-averse and fail slowly like a car crash in slow motion, rather than failing fast and learning from those failures.

In essence, how do we create the right structures that lower risk and allow more rapid iterative development?

To answer that, we must ask… what is our goal?

An open platform is simply the foundation for a longer and much more ambitious journey in healthcare information technology. It is so important to have a vision for a future in 5 or 10 years; we are certain to be wrong, but having ambitious goals and understanding that we’re going to have to change some of our plans; probably the details of some of the steps used to get there; but we won’t be changing the the direction of travel.

So… shouldn’t our goal be to provide the right structures and technology to create high-quality, valuable user-centric applications that can help solve clinical problems, with the “user” being a patient or a professional or other worker involved in care. Don’t we want those applications running now so that we can start work on the next generation of clinical applications. We want to understand our patients and have ready access to tools that support our teams in providing care for patients. Iteration is the key; we will never be finished and there will always be more to do. How can we enable that?

I’ve previously described user-facing applications as ideally being “almost throwaway” in our team meetings here in Wales and such statements have sometimes resulted in looks of incredulity. However, describing applications as “throwaway” simply reflects the following logical chain of reasoning:

- You say I can write clinical applications are “almost throwaway”?

- Therefore, the engineering work must be quite straightforward, because I’m a lazy engineer.

- But surely there is a tonne of clever engineering work needed in healthcare, such as managing users, managing access, looking at patients, managing consent, access logs, getting and storing complex medical information and understanding the status of a variety of healthcare resources?

- Ah! The clever stuff must be already be provided elsewhere!

- So, can you show me the API endpoints and documentation?

The logical conclusion is therefore that we strive for an open platform in which applications coordinate and leverage multiple services provided within the platform; applications are the conductors for our orchestra of services. I expect some core services that are initially, mainly enterprise-bound, provided by individual organisations so that a single application can be deployed with little change between and across multiple those organisations.

However, with time, I’d expect to see a marketplace of increasingly sophisticated “services” that are provided outside of the scope of individual organisations, many provided by commercial vendors, in which sophisticated additional functionality can be made available on a cost per-use basis. Over time, the functionality of “the platform” extends upwards into the cloud increasingly combining traditional data from organisations with new forms of patient-reported, patient-recorded real-life data.

We are already seeing the commercialisation of services like that in other sectors, with Google Cloud Functions and Amazon AWS lambda services providing serverless and maintenance free deployment and scaling of discrete pieces of logic. When are we going to do this for healthcare? Who’ll be first to offer a natural language processing API that takes a legacy clinical document and turns it into a structured document together with mapping to SNOMED-CT for £0.0001 per document? a

As such, I see an “open platform” as stage one of a larger plan, but how do we get started?

What is an open platform?

We’ve been discussing strategy at length within NHS Wales and continue to have a fierce debate about the best way of using limited resources in the most valuable way. Perhaps reasonably, there are some who think we should be concentrating our limited resources on a single all-Wales application, the Welsh Clinical Portal (WCP). I will not cover that debate here, but I feel strongly that a focus on an application is a poor way of meeting both present and future challenges.

So I hope, instead, to influence the national strategy in favour of a platform approach.b For example, at the moment, laboratory and radiology investigation results are available only through the WCP application. We currently tightly bind WCP into our commercially procured laboratory management system and make WCP the only way of viewing those data, allowing other applications to open a separate frame in a web browser “stapling” functionality together.

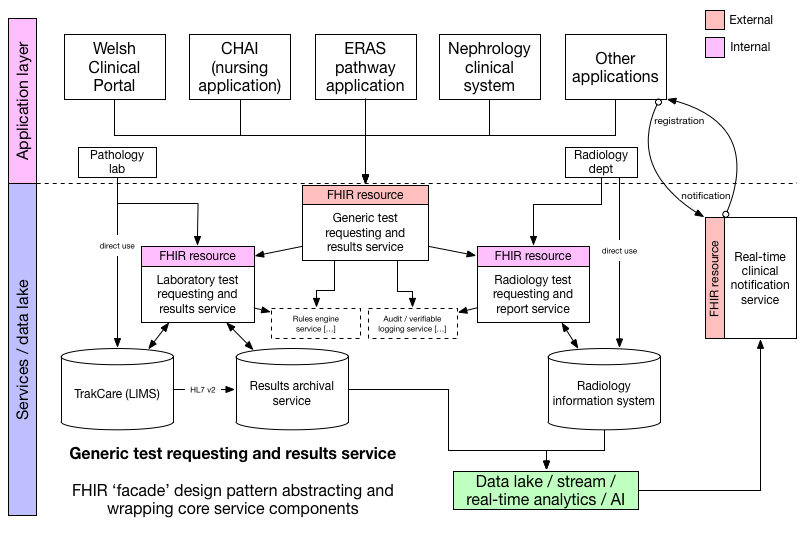

Here is my schematic of the architecture of a more “open” test requesting and results service:

Here WCP is but one view on the same data and same services. Unfortunately, there are some people that think that embedding different parts of an application within another at the user-interface level, using technology such as frames is a better approach. Importantly, such an approach does not expose the underlying data and so fails to support the use of those underlying data in any innovative manner and thus fails to appreciate the importance of data analytics for supporting clinical decision making for an individual patient, managing our clinical services for groups of patients or for research.

The laboratory information management system (LIMS) is provided by Intersystems (Trakcare) and we should replicate that data source in a vendor-neutral archive (VNA) that is exposed to client software via a standardised application programming interface (API). This abstraction is an important tool in making commercial systems a commodity. Commoditisation of components of an open platform is a vital step in reducing vendor lock-in and focusing on what is important; our data and its intrinsic value rather than a product. In this schematic, the VNA is represented by the “results archival service”. Now if TrakCare exposed a standardised API, for example using HL7 FHIR, then it may be that API could be used by the service layer. But the important lesson is that it doesn’t matter, because we’ve abstracted the service. Indeed, the same approach would work if we were trying to provide a unified set of results across multiple laboratories all using different laboratory systems, so long as we built a VNA and carefully managed patient identity between different instances. Indeed, our laboratory colleagues could completely change their systems and our application software does not even need to be aware.

Our business logic is codified at the service level and not the application level and, to manage changes in business processes and clinical need, many of the rules that underpin that business logic should be delegated to a rules engine, which allows business rules to be recorded dynamically in a declarative and not procedural fashion in the language of the business.

I’ve previously discussed the importance of scope; starting with our problem and broadening the scope to create generic solutions. However, that doesn’t mean that we have to build everything in one step. Instead, if we get the architecture right at the beginning, we can offer a laboratory test requesting and results service and then extend the platform to also support radiology requesting and reported as well. The schematic shows this evolution, with a FHIR test requesting service acting as a concierge-type service, taking a request and delegating that request to the appropriate, now private, test service depending on the details of that request.

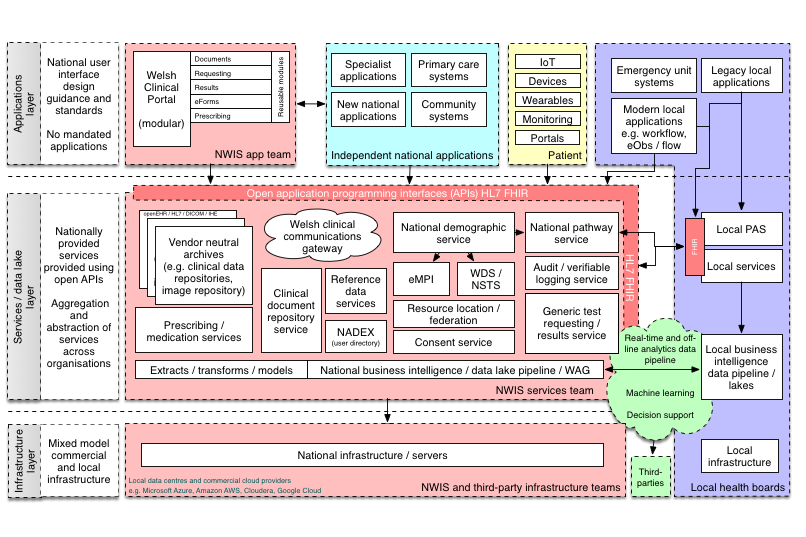

The test requesting / results service would fit into the wider architecture like this:

Once again, a pipeline in which data is extracted, transformed and modelled ready for analytics is critical in ensuring that clinical information is made available at the right time to the right people.

This “platform” shows the important components required by clinical applications, such as patient demography, user management (a user directory which for NHS Wales is a large Active Directory), logging and security, laboratory and radiology test requesting and results, clinical documents, structured clinical information including patient outcomes, electronic prescribing and reference data. HL7 FHIR supports presenting all of these types of data and services as a RESTful API already. As a result, legacy services would require either a FHIR facade to wrap and map that existing service or a method to replicate information to a VNA that exposed that information in a standardised way.

An application written for such a platform, using FHIR end-points to make use of data and services provided by that platform, can potentially be deployed in any environment which provides similar services.

2. Balancing availability and privacy = consent!

It is not difficult to imagine scaling an open platform across multiple organisations and enterprises much like the Internet has scaled so dramatically since its inception with patient data stored encrypted at rest and in transit by those organisations or their proxies and made available to others. The next logical step is to take that information and “make it universally accessible and useful.”

However, there is an important paradox here: we want to increase information sharing and yet preserving privacy and confidentiality for that health information.

As a result, healthcare information technology must consider the use of privacy-enhancing technologies in order to:

- allow safe and secure information sharing between multiple organisations, professionals, sectors and the patient

- give patients the tools required in order to control when and how their information is shared

- provide a distributed, verifiable infrastructure

- support a range of mobile devices used by patients and staff

- maintain the privacy of both patients and staff when mobile devices are ubiquitous.

Patients must have trust that their private and confidential information is secure and yet want that same information available when it is required. As a result, information systems and the way that they are connected must be secure-by-design, with security and transparency built-in as a result of the architecture and networking protocols. Layered upon this infrastructure must be mechanisms to capture patient consent. A private-by-design networking layer would need to implement and support a range of services including:

- cross-organisational identity, for both patient and professionals as well as other parties such as carers.

- multiple pseudo-identities, in which identity may be obfuscated for a particular use to prevent linkage beyond what is permitted.

- commoditising semantic interoperability and data standards

- decoupling of logical systems, including `patient portals’ so that patients not only can choose a provider themselves but then use that portal to communicate and interact with multiple decentralised services.

- networking that does not leak information as a result of analysis of the traffic within it.

- support for innovation, trust and verifiability with `sandboxing’ for health applications.

So my final assertion is that HL7 FHIR is only a component of a wider health informatics strategy. We must consider how to create a single patient record, with information about a single individual made available at the right time and right place when approved by that individual. Fundamentally, this is predicated upon systems to manage identity and patient consent.

Do we rely on applications and third-party services to double-check that they have consent or is it possible to build that consent into the architecture itself as part of how applications and services locate and use resources about that patient? I think the best way of handling this is the use of multiple pseudo-identities which can be linked or unlinked into an aggregated view of a single patient record. In essence, we don’t want to rely on software to have to check whether it can access patient data but instead not even know that data exists or where to find it.

Interestingly, another definition of a “platform” is a set of services that bring together users and providers to form a multisided market. Is it possible then to take our “open platform” and start to think of a future in which we have products and services that actually do enable a re-imagining of healthcare provision to bring together patients, carers, health professionals, commissioners, analytics, researchers and all other stakeholders in a safe and secure manner?

Secure-by-design: sandboxing services and applications

One practical way of considering the problem is to consider how to permit innovation in a safe and secure way and have successful work quickly scaled out across and between organisations. For example, if a new startup company can create tools to automatically identify and monitor patients on drugs such as methotrexate and ensure that they have the required blood tests, how could such tools be deployed safely with certainty as to how, when and why that information was processed with support for an opt-out should a patient not agree to their information being used for that purpose? Can an infrastructure be created that means such applications can be installed in essentially a `sandbox’ in which its interactions with patient data are controlled and monitored automatically? Could that paradigm scale to support access to health data in a generic fashion?

Applications running on Apple’s iOS provide a useful analogy. In order to gain access to components of the underlying device and its operating system, such as the camera, the photo archive, location services etc, the application must use the appropriate API which forces explicit user consent. This “sandbox” environment means that an application is prevented from accessing resources to which consent has not been provided and presumably can log each and every attempt should that be required.

Can we do the same for health applications and services? It seems to me that we can create tremendous value from healthcare data - for patients, for health professionals and for society - but the foundation must be to allow that information to be organised in such a way that we can make it “universally accessible and useful” subject to individual consent.

As I started writing a version of this post back in June, Estonia had just announced its plans for its EU presidency to include the cross-border movement of health data for the purposes of treatment, research and innovation and to promote data-based innovation in healthcare. Creating secure platforms on which such communications can operate would be a pre-requisite for those aspirations.

So what next?

I think that there are several important strands of work, most of which require health organisations and technology companies to work together to use technology as an enabler for the transformation of healthcare:

- work together on joint data standards and both technical and semantic interoperability

- build open platforms to bring together meaningful structured clinical information with data from legacy applications, adopting open standards such as HL7 FHIR and openEHR.

- transform healthcare IT procurement moving away from capital “product”-based procurements to recurring expenditure models based on services ensuring that such procurements are measured against interoperability standards. Procure “products” only when truly contributing to or enabling a larger platform within and potentially between organisations.

- break-down hierarchical autocratic organisations, and instead create highly functionally integrated teams combining skills from multiple disciplines who can take responsibility for achieving their goals; similarly, with such teams we should not be afraid of in-house development work when appropriate.

- explore ways of turning unstructured information into usable and valuable data to explore clinical phenotypes, identify cohorts and use real-life outcome data.

- look to improve the routine real-time use of analytics in healthcare for patient care and service improvement; if we can’t do simple survival curves in real-time for patients having emergency surgery in the last 30 days stratified by age, gender and co-morbidities, then we won’t be able to adopt more sophisticated analytics based on deep learning.

- consider picking niche specialist “vertical” markets such as long-term health conditions, in order to innovate and iterate before taking the lessons learnt to a wider audience.

- take a 5-year (long-term) view and work on applying innovative technology (that probably exists today but just needs combining in interesting ways) into healthcare to support a secure, privacy-enhancing distributed patient record that engenders public and agency trust. I think it has something to do with a high-level abstraction of a distributed patient record, with multiple pseudo-identities bound together by consent with verifiable audit logs and service discovery based on that consent security model.

Why should a technology company be interested in building such an open platform? Because, like the Internet, it will be an enabler and create value for years to come.

Mark

Further reading

- Domain-driven design in clinical informatics

- Organise healthcare information and make it universally accessible and useful

- The hazards of paper

Footnotes

a: Actually, don’t do that, as I’m already working on this using my SNOMED-CT service (rsterminology) and using Google Cloud’s NLP API to identify entities within the text.

b: And hopefully without being sacked in the process.