Designing the future 3/3: the patient

This is part three of a 3-part series on designing future clinical information systems. Part 1 covers the importance of data models. Part 2 covers clinical modelling in relation to process and workflow. This part covers patient portals and the internet-of-things.

So we need to take several steps back from sitting in our clinics and understand what we do and where we are likely to be going in healthcare. Can we model this in an abstract and future-proof way? Can we do what we did when we model a blood pressure, but for something more complex?

It is useful to imagine a patient with several long-term health conditions. These are problems that a patient will have for the rest of their life and most such conditions need ongoing monitoring. This monitoring will be usually managed by a primary care physician or a specialist and their respective teams. As such, several different professionals will be involved, including a range of administrative staff, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, third-sector providers, social services and doctors. These professionals may all work in the same organisation, but it is much more likely that they will work across organisational boundaries and yet need to collaborate and share information in supporting their patient together.

Importantly, a patient is not and cannot be a passive recipient of healthcare. Instead, patients should be active members and leaders of the team, setting achievable goals and defining priorities of care. As such, patients need to be able to interact and collaborate with their teams and not only see the information relating to their care but contribute to it as well. Why do we either not measure outcomes or use surrogate proxy markers of outcomes when a patient can tell us, either directly or indirectly by virtue of their activity data, their prospectively recorded log of seizures or their home monitoring equipment?

So the model of care in which a patient comes for a 6-monthly outpatient clinic is outdated, inefficient and does not respect the patient - placing them in a subservient, passive role in order to receive healthcare. They arrive, sit in a waiting room, have their pulse and blood pressure measured and are weighed and then, as any who has experienced an outpatient clinic will testify, feel their autonomy fade away. We give them an appointment for six months which doesn’t fit with their schedule and will probably be cancelled. Our administrative systems track patients waiting for a new patient appointment, but patients wait for months for another follow-up slot. Information technology alone is not going to solve this, but can we step back and re-imagine our care processes and use information technology to enable that change?

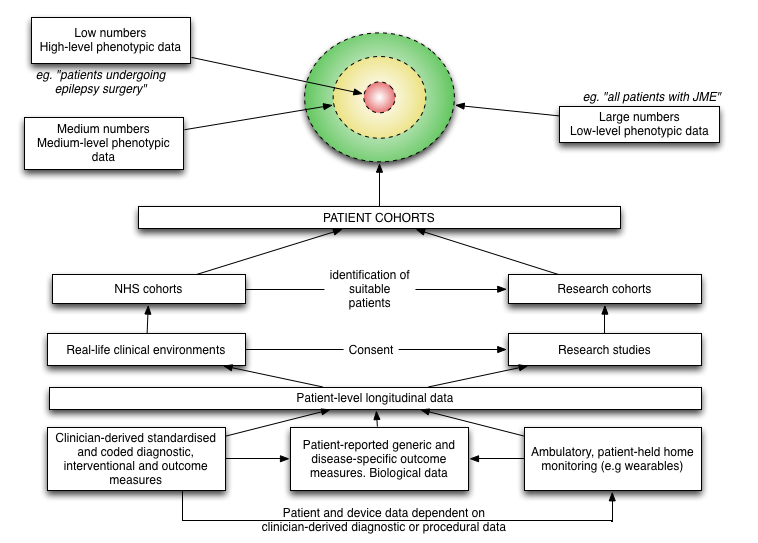

Here is an example overview of how longitudinal prospectively collected information about a patient can be combined from disparate sources:

How can we make sense of step-count data without an understanding that the patient had a hip replacement in May 2017? Likewise, how can we looks at biomarkers on a serum sample taken in April 2017 without understanding the patient had a seizure the day before? We need to integrate, summarise and make available information from multiple disparate sources to the patient and those that support that patient.

If a patient has a clinic appointment in three weeks time, it is possible to have a medical records department that fetches a set of paper notes from the archive and ensures (mostly) that I have them on my desk in clinic at the right time. This model does not scale to support a patient calling us to discuss their care or to support multiple teams looking after patients across multiple disciplines and organisations - who has got the notes? As such, we can use information technology to support a change in the way that we work.

Monolithic architectures

In the early days of the Internet, we had Compuserve and later AOL. As I recall, every computer magazine had a floppy disk or later a CD-ROM with their software on it. Both were proprietary, locked-down portals accessible using a dial-up modem that offered everything from email to bulletin boards to news. As the internet took over, built on open-standards and interoperability, these systems faded into irrelevance and obsolescence. Both tried to react to the more open ‘World Wide Web’ by allowing some degree of information exchange such as permitting emails to be sent and received from the internet, but such limited interoperability was insufficient to prevent the irresistible march of progress.

Healthcare information technology is at a similar level of development to those systems from the 1980s and early 1990s with monolithic systems and single portals pitched as the solution to all healthcare problems. Large-scale enterprise applications (such as Epic and Cerner’s Millenium) are now installed in many hospitals and these have started offering limited interoperability in order to make their data available to other systems.

Similarly, those systems can offer a patient portal in which patients themselves can login and interact with that organisation and its teams. In addition, there are now increasing numbers of more consumer-focused patient portals acting as “personal health records” (PHRs) such as Patients Know Best, Microsoft’s HealthVault and Google’s (now closed) Health PHR. An overview of the use of PHRs was written by the Royal College of Physicians’ Health Informatics Unit in 2016 with a focus on PHRs provided by healthcare organisations themselves. In all cases, these products create portals to which patients may interact, and their use is principally communication between the patient and their healthcare team.

The advantage of a monolithic system is that the patient portal can encrypt all communications between itself and the patient or their device(s) and appropriately manage the secure transmission of clinical information to and from other clinical systems within a wider healthcare enterprise.

The disadvantage of a monolithic system is similar to the problems experienced by users of closed systems like Compuserve and AOL; they are locked into using that system and potentially innovative smaller enterprises become excluded from the market. If a particular provider does not support data from a particular device, such as a new product to detect seizures occurring in a patient as they sleep, then that patient cannot share that data with their healthcare team. Finally, which system should be used? Should the patient choose? Should the organisation choose? And what about patients who are looked after by multiple organisations?

Can we do better?

The problem with healthcare data is that it is private and sensitive. So how can we make healthcare data more open and more accessible and yet keep that data safe and confidential? How can we connect the patient and their devices and everyone else involved, whatever their organisation? And if we want to make healthcare data more available, won’t we exacerbate our existing explosion of data and will need tools to make sense of that information. I don’t want to have to read through all of the day-to-day nursing notes recorded when a patient was an inpatient to find that critical piece of information.

We need systems that can make health information more widely available within our NHS network between NHS organisations, but that is insufficient. We also need to extend our reach to the patient, to other care providers such as social services and the third-sector.

So, what do we need?

- A secure but open distributed infrastructure:

- Solve the seemingly mutually exclusive goals of security and availability. I think the answer will have to come in a future blog post, but we need to consider how to make a secure, distributed, decentralised infrastructure on which open standards permit semantic interoperability between disparate systems. We think that there are some clever ways that this might be achieved.

- Can such a system adopt both a messaging function, in which electronic communication can be sent securely from one end-point to another, but also a publish-subscribe (multicast) model in which different services contribute and receive information about their patients?

- Support data standards and semantic interoperability with clinical modelling for data and process:

- Build tools to capture structured data at the point-of-care, and make entering structured data easier to do than entering unstructured free text.

- Build tools to turn unstructured data into structured information by advances in natural language processing.

- Build tools to support making sense of large amounts of unstructured and structured information in a variety of different clinical, professional and personal contexts.

- Understand what we mean by a clinical service and a team, not defined by an organisation but how they work together for a patient.

Essentially, we need an “information superhighway” for healthcare, in which we can exchange communications securely and yet privately between multiple end-points.

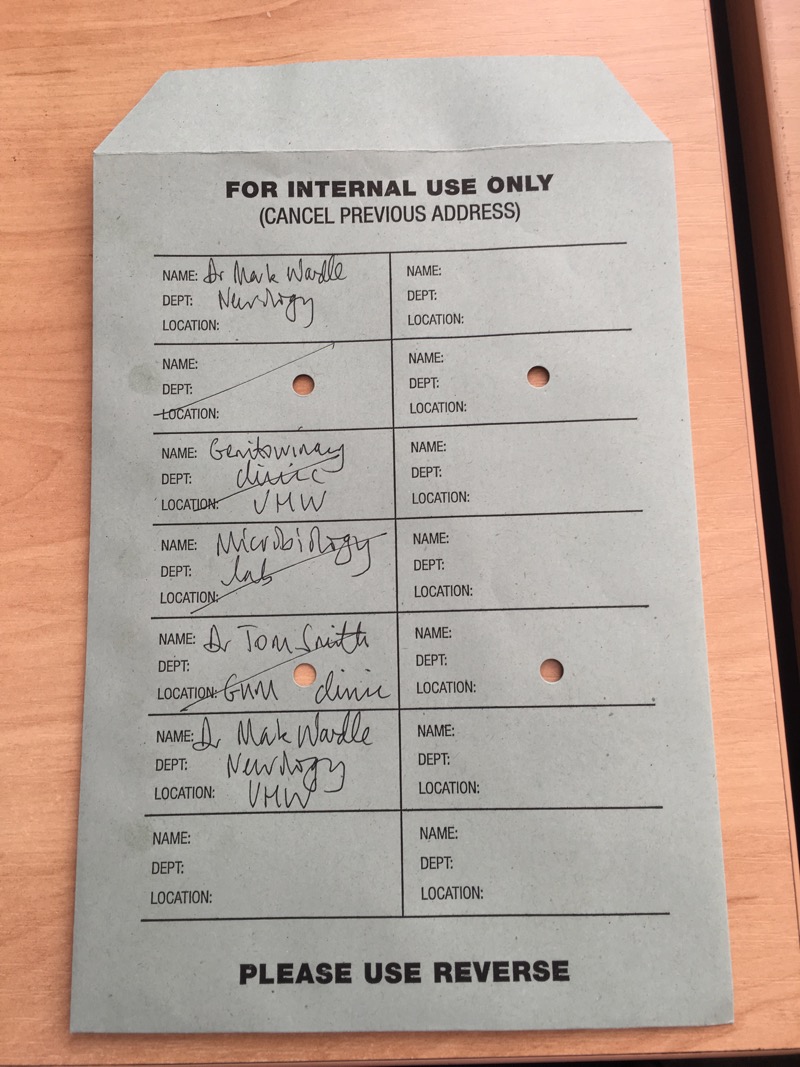

One of the problems with the secure exchange of information is that, while we can encrypt the contents of my message, the metadata (data about data) leaks confidential information:

In this rather contrived example, you can see that I sent some information to the genito-urinary clinic and then received some information back. You can guess that a result was included as the laboratory has also been involved. You don’t need to see the contents to make some inferences about what is happening.

Leaking information via your metadata is even more problematic for electronic communications. If my patient sends and receives electronic communication to a HIV helpline address, that information tells me something important and leaks private information.

Any distributed system connecting patients and their devices to our healthcare enterprises needs to solve this privacy concern.