Safely deploying machine learning in healthcare 2/2

I have previously discussed the value of information technology in supporting clinical care, unashamedly stealing and modifying Google’s original mantra:

“to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”.

and adapted it to healthcare information:

to organise healthcare information and make it universally accessible and useful

and argued that we should be making healthcare safer by running it on rails.

I want to talk about artificial intelligence and healthcare in relation to measurement, data and decision making. I outlined the regulatory issues according to the MHRA of the application of AI in healthcare in a prior blog post..

Decision making

Why is information important? At its most fundamental, healthcare is about decision making. As such, I would argue that making the right information available at the right time is critical in reducing the uncertainty around any decision in healthcare.

I am reading “How to measure anything” by Douglas Hubbard. It is not primarily written for healthcare, but instead focuses on how to use measurement to reduce the uncertainty around business decisions with a particular emphasis on the importance of what is measured.

Decision-making in healthcare may be relating to the diagnosis or treatment of an individual patient but just as importantly relates to decision-making for groups of patients when we are making decisions about the design of our healthcare services.

From Douglas Hubbard:

In business cases, most of the variables have an “information value” at or near zero. But usually at least some variables have an information value that is so high that some deliberate measurement effort is easily justified.

In medicine, many of our “measurements” (facts gleaned about how a symptom developed, results of investigations) have very high “information values”. Others have very little.

Now I have regularly argued that we should be routinely recording structured information about our patients including information relating to problems, diagnoses and outcomes. Such data then allows us to make appropriate inferences about our patients such as, how is this patient doing compared to other patients with this condition? In many clinical situations, identifying the patient not behaving as expected is important.

In fact, many of our current “measurements” in healthcare relate to information easily acquired, rather than measurements of value. Before deciding on measurement, he opines:

- What is the decision this measurement is supposed to support?

- What is the definition of the thing being measured in terms of observable consequences?

- How, exactly, does this thing matter to the decision being asked?

- How much do you know about it now (i.e., what is your current level of uncertainty)?

- What is the value of additional information?

If you are recording information (making measurements) that do not support decision making and that information has no intrinsic worth itself, then why are we asking/examining/performing/assaying/recording it at all?

Reducing uncertainty

So if we decide that a measurement is worth doing, do we need to perform that measurement on all patients in order to make appropriate conclusions? The answer of course is no. We saw this in the recent UK general election in which an exit poll correctly predicted the outcome based on sampling a small number of voters (100-200) at each polling station.

Accordingly, decision-making relating to groups of patients, particularly in relation to how we configure services or apply limited resources to populations of patients, does not need measurement of all people within those populations in order to reduce the uncertainty relating to those decisions. Instead, it is reasonable to perform those measurements on a random sample. A random sample is, however, not a sample based on a subgroup of patients who have volunteered to take part. Such a sampling methodology will introduce bias in your results. Instead, sampling should, ideally, be a random sample of individuals

Now these three propositions are outlined in the book (I have reworded them slightly to suit medicine):

- We care about measurements because measurements inform uncertain decisions.

- For any decision or set of decisions, there are a large combination of things to measure and ways to measure them—but perfect certainty is rarely a realistic option.

- Therefore, we need a method to analyse options for reducing uncertainty about decisions.

Using AI to reduce uncertainty

In healthcare, we have a problem with information overload. I must manually scroll through laboratory results looking for something relevant, and in the current (nationally-provided) software I have to use, one has to actually click to open each individual result to check what it showed.

So we can refine our needs to include the importance of displaying the right information at the right time. In other words, which “measurements” to show at a given time point that will most reduce the uncertainty relating to a decision.

While machine learning holds the promise for creating tools that can make clinical decisions inferences independently or semi-independently, I would argue that information technology should focus on valuably supporting care by organising and presenting information about patients to patients and clinicians and providing intuitive adaptive tools that allow the systematic recording of clinical information.

There is considerable hype relating to AI in healthcare, but this risks overlooking concrete and tangible benefits in the short-term to augment and support humans, whether patient or clinician, in healthcare.

Such goals may sound mundane compared to the future possibilities of machine learning in healthcare, but to clinicians and patients who have spent many years being “information-poor”, the power of having all relevant information available on hand as well as adaptive tools to record that information quickly and efficiently should not be under-estimated.

Imagine a patient admitted with weakness as an emergency. An acetyl-choline receptor antibody test was requested by the general practitioner four weeks ago before the patient deteriorated quickly. Do you think the admitting team will notice that result sitting in the laboratory? At the moment, it will be left to luck. How can that be?

Instead, adaptive, learning, intelligent systems should be able to curate medical information (our “measurements”) in order to reduce uncertainty (in this case, our diagnosis of myasthenia gravis).

We could try to manually curate the rules behind adaptive information displays with complex if…then statements, but ML offers scope to learn from clinicians. For example, real-time adaptive systems could learn what clinicians click on in different circumstances, “see” that patients are having repeated blood tests after a surgical procedure and then subsequently “understand” that it is useful to graph them. Like Amazon can suggest other things for you to buy, adaptive displays of information can “learn” to present the right information at the right time.

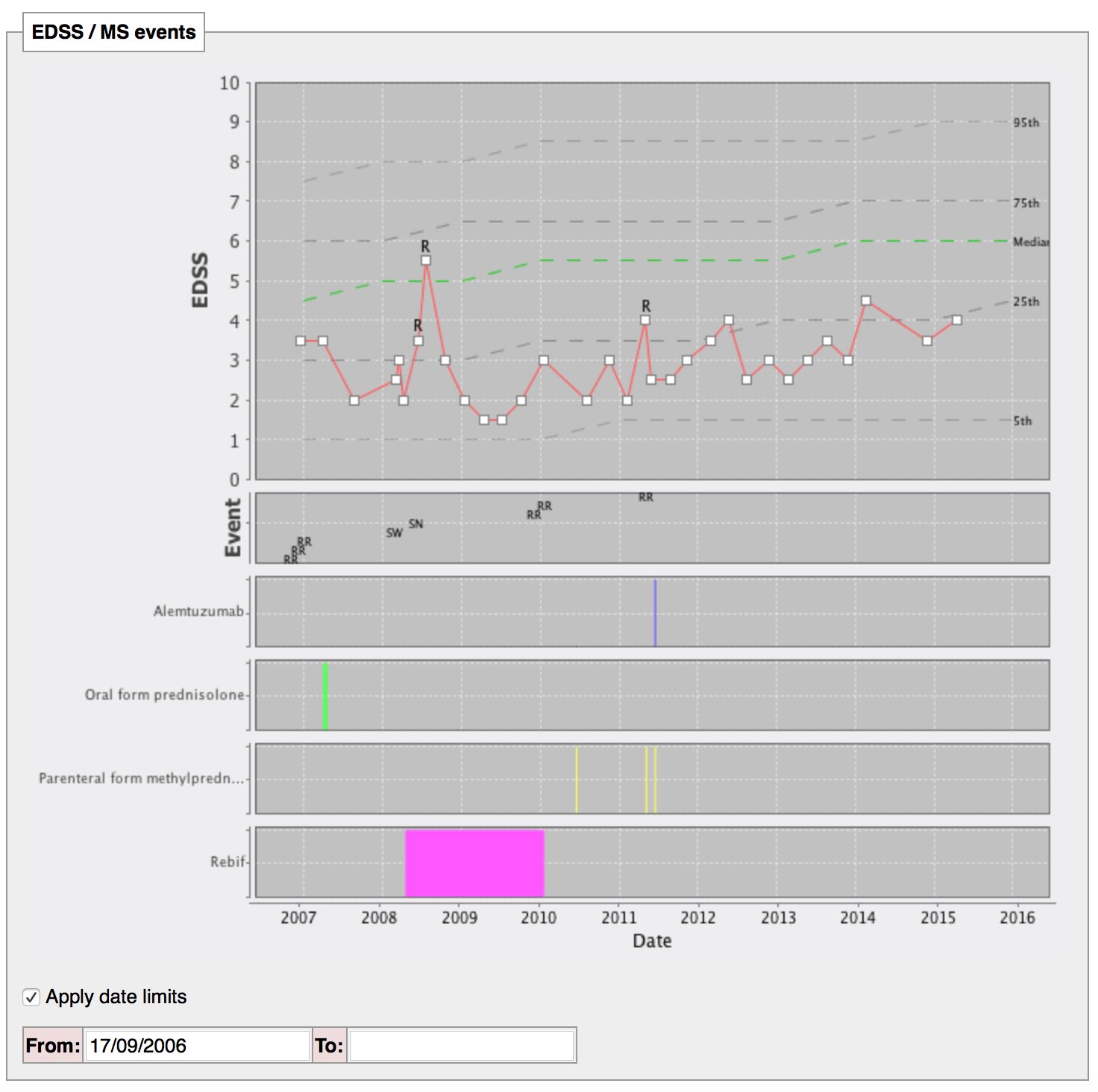

For example, you have multiple sclerosis? Here are your outcomes over time compared to patients like you of the same age:

I have built that manually, but why can’t machines curate the information for us?

Bayesian logic

Healthcare professionals regularly use tacit rules to arrive at clinical decisions based on a set heuristics which will include ‘a priori’ knowledge applied to individual patients. For example, if I know Wilson’s disease is rare but treatable, I will attempt to diagnose it more frequently that something rare but untreatable. Likewise, if a condition is common, then I will test for it more frequently. Likewise, no investigation or diagnostic test is foolproof, with false positive and false negative results. Bayesian inference is a way of adjusting the probability of a hypothesis (eg. my patient has Wilson’s disease) based on a combination of `a priori’ knowledge (e.g. its prevalence) combined with new information.

However, in clinical practice it is difficult to truly understand the significance of new information. Just as we need to make information available, we also need help in deciding whether new information (“measurements”) are relevant to the clinical decision we face. As a result, we need technology to identify ‘a priori’ knowledge and support us in interpreting how new data influences our clinical decisions.

Conclusions

In conclusion therefore, AI can valuably support healthcare by making the right information available at the right time, and learning how to present that information in the appropriate way to reduce the uncertainty relating to clinical decisions. In addition, adaptive systems can usefully identify the “measurements” (data) required to further reduce uncertainty, leveraging ‘a priori’ knowledge and appropriately adjusting to an individual scenario.

As such, we need clinical information systems that enable health professionals and patients to make inferences and support clinical decision making, and AI can and must play a useful role in supporting those systems.

Further reading

- Organise healthcare information and make it universally accessible and useful

- Making healthcare “run on rails” - the importance of technology

- Regulatory issues of the application of AI in healthcare

- “How to measure anything” by Douglas Hubbard

Mark