Balancing information governance and innovation in the NHS

“Google’s Deepmind made inexcusable errors handling UK health data”, was reported on 16th March 2017 in an article published in the journal “Health and Technology” by Julia Powles and Hal Hodson. The article is here.

I don’t agree with most of their conclusions and there are some factual errors. One example is that they suggest that because the application is used in the monitoring and treatment of acute kidney injury (AKI), that access to data on patients not identified as having AKI is inappropriate and should need explicit patient consent. The error here is obvious to a practising clinician: namely, one cannot monitor and identify AKI without monitoring the renal function of all patients. They suggest that patient data should be shared only for patients who have had a “gateway blood test that is prerequisite for AKI diagnosis”. Again, a renal function test (commonly called renal profile or urea and electrolytes), is one of the (if not the) most common blood test performed in hospitals and certainly none of my patients have escaped having this blood test! In addition, the absence of a previous test may itself be a signal potentially of use in future implementations of AKI alerts; an absence of data due to a process that deliberately withholds such data may result in systems to support clinical care that are less valuable than systems having access to a complete set of data.

My blog isn’t the right place for a detailed review of this article, but one positive conclusion is that we need to have a conversation about health data and the potential benefits and pitfalls of sharing. I’ve referred to the care.data fiasco in a previous blog post and, speaking in my role as a full-time clinician, we need to avoid any further controversy.

Information technology in healthcare

Are there any benefits to the more effective use of information technology in healthcare?

In my opinion, very much so!

Many of my patients will give an account of information not being available at the point-of-care, complicating their care and resulting in frequently needless duplication of care. From a personal point of view, I worry about starting drugs such as methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate as these treatments need ongoing monitoring with checks of renal function, blood counts and liver function on a regular basis. You may be surprised to hear that there are no systems in place to ensure that this core work is performed. I don’t even get results sent to me, so I have to remember to login to my computer and check the results manually. Will I make a mistake? Definitely. Many specialties which use these drugs more frequently than my own (neurology) have a dedicated specialist nurse whose responsibilities include monitoring these bloods. But why have a human doing a job that a computer can do more reliably?

Driving off-road vs. taking the train

My day job is looking after patients with neurological diseases such as epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and motor neurone disease.

I have frequently compared the process of my work to “driving off-road” - travelling in uncharted territory - in order to get routine things done. Yet I find myself having to do this again and again when in fact, most of what I do should be a case of “taking the train” - medical care on rails, automatic, on-time and efficient.

My colleagues and I will always need to “go off-road”, but this should be the exception and not the rule; importantly, it frees us him to concentrate on those patients in which we truly do need to go into uncharted territory. We therefore need tools that bring together the right information at the right time, but make logical inferences from those data in order to improve patient care.

Technology and medicine-on-rails

In summary therefore, I want most of my work to happen “on rails” and, like many of my colleagues, have become frustrated with the agonisingly slow introduction of technology into healthcare. There are already many companies providing solutions in use in community and hospital services but I am worried. It is increasingly difficult for small and medium enterprises to enter the market and ongoing consolidation has resulted in very large companies providing enterprise-wide organisational-bound applications such as Cerner’s Millenium and Epic. The Wachter report is an excellent blueprint for the future of IT within NHS England but like others, I have noted that the approach has a focus on secondary care services, will result in a small number of very large vendors monopolising the market and doesn’t really cover community and social care.

In addition, a focus on large single-supplier products for each organisation results in a national architecture that will have a natural tendency to use a health information exchange as outlined in “Section 5.14 Are there exceptions to the use of a layered architecture?” of my Domain-driven design document for clinical information systems. Instead, I want an influx of new vendors, able to access data in a safe and controlled manner, using an open healthcare platform, to add value and benefit to clinicians and, by extension, to patients themselves.

The logical questions that arise from this are:

- how do we permit the adoption of small, well-defined applications within the health enterprise in a safe manner?

- how do we permit access to large-scale aggregated health data in a way that benefits both individual patients for their direct care, and groups of patients at a population-level?

For example, if I wanted to introduce a small, well-defined application that would a) identify my patients on methotrexate, b) monitor their bloods for me, c) request their blood tests at the right time, if they haven’t already been done and d) alert me when they don’t have their bloods or they have a blood dyscrasia or some other change which merits my attention, then how could I do this within the current NHS infrastructure?

For example, if a large commercial entity with expertise in artificial intelligence wanted to add value by monitoring a cohort of patients automatically to identify acute kidney injury, then how can this be done that satisfies both regulatory requirements and defends against public concern?

The case for pseudonymisation

Pseudonymisation is a process in which identifying data relating to an individual is replaced with an identifier. A commonly used method of pseudonymisation in healthcare is to create a pseudonym using a recipe based on fixed unchanging information about a patient such as a national identifier, a date of birth and country of birth. This uses an important property of a hash function to generate a fixed-length digest of a variably sized input; it is mathematically a one-way process. If you give me the input then I will always obtain the same digest but, given a digest, I cannot determine the input.

Now that last statement is not quite true, but brute-force attacks on hash functions are outside of the scope of this blog post, and, as long as one uses an additional salt (a fixed input parameter used together with other input parameters), one can avoid pre-calculated lookup table attacks.

For example, one might generate a string such as “WIBBLE-111111111-2000-01-01-BIRMINGHAM” (a salt, the NHS number, the date of birth, the city of birth), and then use a SHA-256 hash to generate a unique digest.

Pseudonymisation is different to anonymisation in which all identifiable information is removed. With pseudonymisation, it is possible to subsequently re-identify an individual. If an “attacker” knows the recipe for building the pseudonym and the salt, then they too can generate the pseudonym independently and subsequently use that pseudonym to link to data about that individual.

Of course, if an “attacker” knows the recipe and the salt (together acting as a shared secret) and the individual’s information already, then one might assume that they are permitted to look-up information relating to that individual.

Importantly, a different pseudonym can be calculated depending on what we are trying to achieve and to which other data our data need to be linked.

Healthcare data on a need-to-know basis

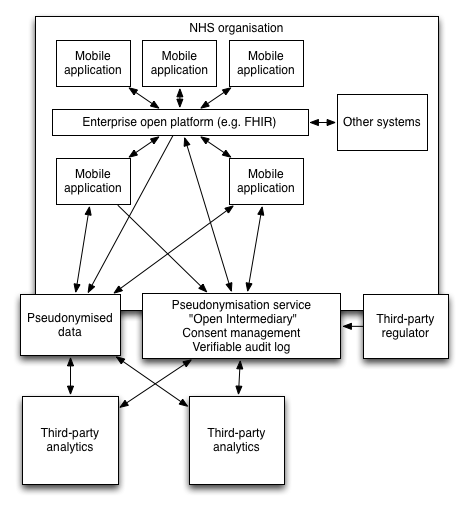

This figure demonstrates how a trusted pseudonymisation service can act as an intermediary between an NHS organisation and trusted third parties.

Here, the mobile devices are, without doubt, involved in direct clinical care. For that reason, they may directly interact with trusted organisational systems, supporting the management of patients. Importantly, they act as a proxy for a clinical user, supporting authentication and authorisation and then allowing that user to navigate health information as required.

However, we would like to make use of health information to track patients with acute kidney injury. Instead of transferring patient identifiable information directly, we generate a project-specific pseudonym for this purpose only. With this identifier, a variety of information can be shared with the “open intermediary service”.

Third-party analytics cannot re-identify patient data but can use health data to support clinical processes. Importantly, they can push information back to the trusted intermediary again linked to the individual using the provided pseudonym

It is only within the NHS organisation that software can link the pseudonym-linked data with the identifiable information. The mobile application for example, can generate a pseudonym dynamically and request information from a third-party without giving away any information as to who or why the information is required. In addition, a third-party may generate an alert linked to a pseudonym and an NHS hosted service can re-identify the data.

In addition, any third-party analytics must obtain healthcare data from the trusted open intermediary which contains only pseudonymised information. As part of a request for information, the intermediary may use a verifiable append-only audit log to record that the request has taken place. Once again, only software running within the NHS can identify to whom an audit log refers and thus, this information can be shared with both the patient and the host organisation. A third-party regulator can act to routinely verify that audit logs within the open intermediary service have not been subject to tampering.

Scaling

Using this system, it becomes possible for many different projects to use patient data without needing to handle patient identifiable information. Importantly, with a different pseudonym used for only a specific purpose, it is not possible for any individual project to link to data that has used a different pseudonym for a different purpose.

If there were a centralised NHS-hosted service that recorded participation in projects, whether for direct clinical care or for research, then only that service could generate the required pseudonyms in order to re-identify or link data from disparate systems. In addition, patients themselves could control to which projects they are happy to share data.

For my methotrexate monitoring application, we would need to identify all patients on methotrexate as well as look at their laboratory investigations. For this, we need medication histories as well as renal and liver function tests together with full blood count results. It is conceivable that this clinical application could easily be regarded as direct clinical care and so use a global pseudonym and share information with other applications. However, it would be possible to generate a project-specific pseudonym and use that together with the required clinical data for analysis by a third-party.

Complex analytics may then occur inside or outside of the NHS services. Interestingly, if data are sourced from multiple organisations for the same project, they can be safely linked together without needing the third-party to perform re-identification. Each organisation would send clinical data bound to the same project-specific pseudonym. As such, the pseudonymisation service can scale to support multiple organisations and allow inferences to be made across data from those organisations.

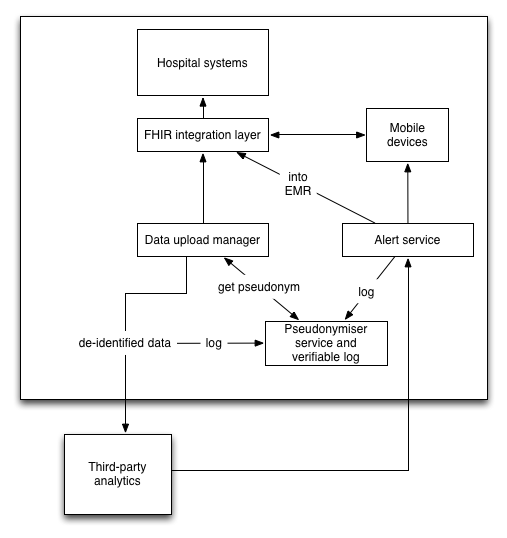

This schematic shows what might happen for an AKI alerting service.

Here laboratory data are taken from source systems, given a project-specific pseudonym and send for third-party analytics. The pseudonymisation service stores the patient information as well as all of the pseudonyms in use as well as patient explicit consent for inclusion (for research) and withdrawal of consent (for direct care). A log is created.

If there is an AKI alert, a third-party sends back an alert to an NHS hosted service. This identifies the patient using the pseudonymisation service, allowing further logging of the results of processing. Now re-identified, the alerting service may link to the EMR and any mobile devices in order to notify the team.

Centralised vs. distributed pseudonymisation

Readers may be familiar with the SAIL databank hosted by Swansea University. It uses pseudonyms to perform data linkage from multiple sources. It is a centralised pseudonymisation system, performing analysis is much like working in a smoke cupboard as one needs to use a remote desktop to run R and one cannot take data out of the closed system. In addition, a lot of the datasets were rather old when I last used the service. It is working however, and has avoided many of the controversies commonly seen when aggregated medical data is used for non-direct care purposes. One takes a clinical set, splits it into two parts containing patient identity in one and non-identifying information in another. The two are linked with a unique identifier. A secure NHS service performs the pseudonymisation and the non-identifying information is placed in a data warehouse with the pseudonym. They use a global pseudonym which allows linkage to other source of clinical data.

For example, we used SAIL to show that the main risk of a further attendance in the emergency unit for a patient with epilepsy was their social deprivation.(Lynch E, Lacey A, Pickrell W, et al FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH EMERGENCY ATTENDANCES FOR EPILEPSY J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:e4.) by linking emergency unit attendances with general practitioner records and socio-economic indices.

The problem is that this is offline analysis suitable for retrospective analyses. This will not support real-time analytics or any of the innovative supporting technologies that healthcare today needs.

It is here that I need help. Is it possible to create a distributed system to track patient consent for research, to provide distributed pseudonymisation and verifiable audit logs of access to data? Ideally, we would not have a centralised pseudonymisation service or a centralised audit log, but distributed systems that both maintain patient confidentiality and provide assurances as to the use of data ideally replicated among trusted organisations.

My final questions are therefore:

- Can Merkle trees be used to implement a verifiable audit-log backed key-value store service within the NHS network to store consent and access logs?

- Who will act as a guardian of this service and monitor the logs?

- Could this act as a pseudonymiser service, logging the pseudonymisation and the upload of non-identifiable clinical data?

- Similarly, when sending data back to the NHS, could this pseudonymiser service act to link data back into the patient’s record, logging such access?

- Would such a service support the safe use and monitoring of third-party applications and data analytics?

I would be grateful for your thoughts.

Mark