Embedding data in routine clinical practice

I spent today at a medical conference relating to motor neurone disease. Today’s conference reinforced my previously held beliefs about the best strategy for healthcare information technology improvement.

At the conference, we had a mixture of health professionals and academics, all struggling to do what they need to do. The nursing and care coordinators desperately need tools to support their day-to-day work, managing patients and recording their interactions and communicating with one another. The Motor Neurone Disease Association (MNDA) want them to use Excel spreadsheets to audit their services for benchmarking and assessment against the NICE guidance. The researchers in the room want a population-based registry in which patient data are recorded to support national history modelling, epidemiological students and subsequently act as a platform for subsequent interventional studies. We heard about researchers collecting patient reported data using paper and pen.

This pattern recurs again and again and I’ve referenced the three core needs of:

- supporting day-to-day clinical care,

- audit and quality improvement and

- research

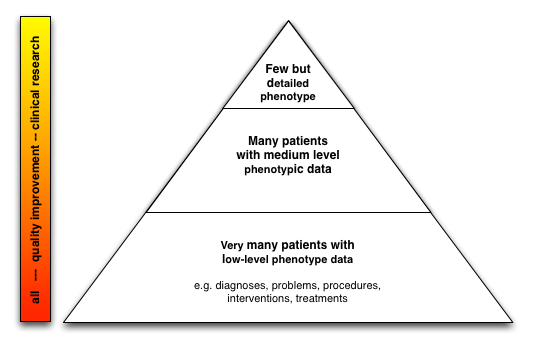

in my blog posts repeatedly: (eg see my post on patient safety). This approach is not specific to motor neurone disease and is widely applicable. The critical issue is to embed the three processes within the same system so that, for example, a clinician recording research-level detailed phenotypic information about a patient for their area of interest uses the same system as the one that he or she uses to simply record a register of diagnoses. I think of a nested approach in one has small numbers of very well phenotyped patients and large numbers of less well phenotyped patients.

An important component of this approach is increasing patient involvement in research. Patients want it but there are impediments such as the time needed to obtain patient consent and the resources needed to perform more detailed clinical evaluations. As such, using technology to support enrolment into clinical research is vital; that is, we must provide tools to obtain consent from large numbers of patients in a way that satisfies the regulatory frameworks in which we work.

Similarly, we are increasingly using patient-reported outcomes and adaptive questionnaires to not only understand how our patients fare but even to shape subsequent clinical consultations.

So it becomes straightforward to imagine an architecture that will support these needs. Indeed, if built correctly with a generic core, a standardised terminology and bolt-on specialist modules, one could imagine it being a disruptive product, creating a commodity platform. I want to see a future in which the platform becomes an interchangeable commodity with innovation and differentiation occurring at a higher conceptual level of support for medical practice. Rather than simple data collection, our mission must be to imagine a future in which medical practice, which at its most fundamental is about clinical decision making, is supported by the most sophisticated tools possible to improve patient care.

This mission’s greatest risk is in the continued creation of data silos in which health information is locked away in proprietary systems. The answer is to create an open, extensible platform on which innovation can thrive.

I would draw a parallel to the evolution of the Internet. In the early days of computer networking, there were many proprietary networking protocols. The advent of TCP/IP and the creation of an interoperable but layered architecture in which at the highest conceptual layer, lower level details of networking were abstracted has resulted in the thriving interconnected Internet as we know it. Similarly, we need create abstractions of our high level clinical requirements but take into account the complexities and paradoxes required in order to share private confidential medical information safely.

Minimally viable products

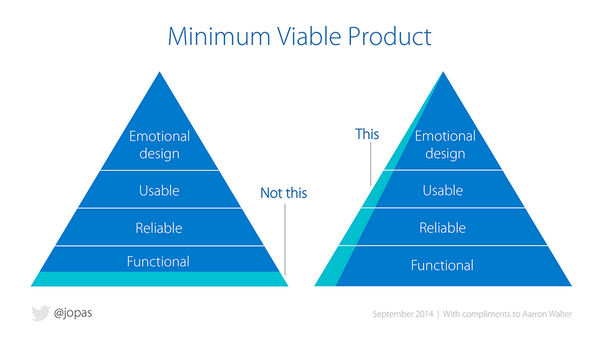

I have always liked the concept of minimally viable products (MVP) in which one works to prove a methodology or design by creating a minimal proof-of-concept and running it in the real world

I have built my own electronic patient record system and think it is essentially an MVP for healthcare information technology, although perhaps it has now better regarded as an actual product given it is in-use in live clinical environments.

In general, clinicians need solutions that solve their problems, and that will vary depending on their role, their speciality and their particular interests. While clinical practice and research are separate processes, having a single system that supports the collection of clinical and research data in different contexts but as part of the same record has been a powerful and valuable tool.

Essentially:

- it is an NHS-hosted web-based electronic patient record system already in use for 8 years

- it now records 3000 clinical encounters every month by a wide variety of multidisciplinary teams, recording structured clinical information and embedding SNOMED-CT into clinical practice.

- it links to multiple PAS within different hospitals and sends clinical documents into a document repository

- it allows flexible data collection configured at runtime to support multiple cohorts of patients and the generic and disease-specific outcome measures. As such, it is used widely for multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, metabolic disease, neuromuscular disease, motor neurone disease. It is about to be used for adult cystic fibrosis services.

- it uses SNOMED-CT as a lingua franca to allow loose-coupling between components and switch functionality on and off in different clinical circumstances.

- it provides an Internet-hosted portal for patient reported outcomes and mobile device management

- it has client iPad applications to collect patient reported outcome measures and obtain patient consent using Apple’s ResearchKit software.

- it can send alerts if patients lose weight or are admitted to hospital, based on an understanding of defined cohorts for long-term health conditions.

- it can generate clinical correspondence automatically from data entered during the day-to-day processes of clinical care

- it acts as a communication hub between different members of the team, with messages linked to the patient record

I’m now working on scaling out this suite of products and the underlying data-driven principles of the architecture more generally. My goal is to create an open, semantically interoperable architecture for healthcare.

Mark