Using data for patient safety

This blog post is from a talk I gave to the RCPE in December 2016.

In healthcare, we use data for:

- the day-to-day care of individual patients

- the management and governance of our clinical services

- to support clinical research and innovation.

As such, the effective use of data is critical for patient safety, both now and in the future. So, you might expect healthcare services to have highly developed systems to allow the recording of structured longitudinal observational data?

Well, no we don’t. Instead, we largely have expensive paper records, poorly accessible with no support for team working. Paper records frequently end up poorly structured containing lots of data but in a format difficult to use in any systematic, safe or indeed automated way.

Supporting your practice

“You’re a victim of it or a triumph because of it. The human mind simply cannot carry all the information without error so the record becomes part of your practice”

“if you can’t audit a thing for quality, it means you do not have the means to produce quality”

Dr Larry Weed, Internal Medicine Grand Rounds, 1971

The information in the medical record isn’t something separate to the day-to-day care of an individual patient or indeed a group of patients, but instead is part of that care. However, we clinicians have historically been neglected and the information we need to run our services is not available in a routine and systematic way.

We should not capture information unless it is useful and, as its most fundamental, data are only useful if they influence a decision or reduce uncertainty in relation to that decision, whether it is a decision for a single patient sitting in front of you or a whole group of patients sharing some defined characteristics.

What is already collected?

Since the Korner report was published in 1982, there has been a commitment to routinely collect a national set of data for the management of the NHS.

As a result the health service does collect lots of data, such as the hospital episode statistics (HES):

It is illuminating to read contemporary criticism of that report such as that from Sir Douglas Black, then RCP president who noted:

“the focus of the inquiry seems to have been on the use of information in management, not in any way as a criticism (improvement in management is both possible and desirable) but to underline that the report must be judged in that context and not in relation to other uses of information in clinical medicine or clinical epidemiology.”

“The recommendation that diagnostic data should be collected on all patients covered by the system is to be welcomed; its omission would make these scheme even more obviously a management exercise, thereby lessening its appeal to the active clinician” (my emphasis added)

Sir Douglas Black, 1982.

I think it is reasonable to say that the majority of clinicians have not engaged with these data, nor have they used those data to support their own practice or indeed plan their own service developments. In addition, while there are clinical coders recording diagnostic and procedural codes for inpatient episodes of care, no such information is recorded for outpatient clinics. As a result, we know how many patients are seen in our outpatient clinics, but have little idea why they are seen or how they fare. Importantly, most hospital patient administrative systems do not record information relating to any other type of patient encounter, such as telephone callsa, home visits or electronic communication.

The limitations of HES data have been widely known; perhaps the most important limitation is that it is incomplete. As a result, those data bear little resemblance to what happens in real-life, do not recognise team-working and are not recorded by health professionals. Consequently, health professionals rarely see the data, and when they do, they scoff at its inaccuracy.

But this isn’t of only academic interest; this is serious and important to our health services.

Please read this extract from the Bristol children’s heart surgery report 16 years ago (2001). Are you confident that we have addressed this within the NHS in 2017?

The various clinical systems, many of them paper based, differed from one another and had no relationship with the administrative hospital-wide systems. The funding made available in the late 1980s and early 1990s for medical and later clinical audit helped to reinforce this separation by making available to groups of clinicians money for small local computer systems. The lack of any connection between these different systems, one administrative, the others clinical, for collecting data cannot be explained solely on the basis of some technical or technological reason. It was just as strongly a reflection of a mindset that clinical matters were the sole domain of clinicians and non-clinical matters, to do with the management of resources and with the movement of patients into and through the hospital, were the preserve of managers and administrators.

So, is the answer another registry?

The answer for many clinical services appears to have been the creation of bespoke, specialty or disease-specific registries. Such registries are often created by a particular medical or surgical specialty, a disease-specific organisation such as a charity or an academic centre looking to build a cohort of patients for clinical research.

The problems with dedicated disease or speciality-specific registries are:

- there are lots of them, so potentially lots of disparate systems

- not embedded in day-to-day workflow

- sometimes little feedback, result or reward, particularly in any timely manner

When I am in clinic, I might see consecutive patients with epilepsy, chronic fatigue syndrome, headache, and then multiple sclerosis. How can I possibly use a different clinical system for each individual patient, and what should I do if a patient has more than one problem!

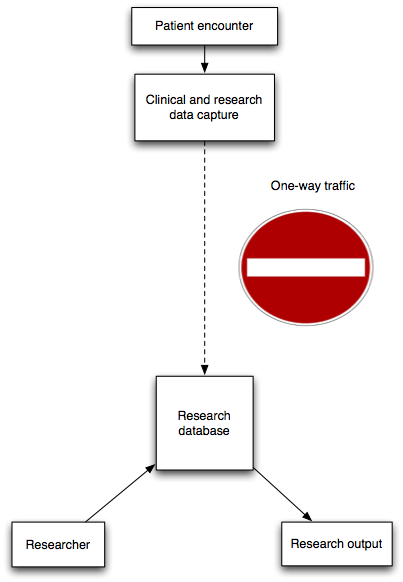

The most important disadvantage is the lack of timely feedback for users. All clinical systems must provide value to the users of that system, with the value of a system arithmetically divided by the length of time it takes to return that value back to the user. If I am going to spend time entering information, that information must create value immediately so that we create a virtuous cycle of continuous data improvement.

For example, in stroke medicine, we have the Sentinal Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP). This is a large-scale national audit project in which teams of health professionals perform notes review, completing data collection forms answering questions to derive data on outcomes such as “Median number of minutes per day on which physiotherapy is received”. The aggregated results for a region and comparison of these indicators with other regions are then disseminated months later.

Instead, we need systems in place that can answer that question for our current inpatients today so that, for this example, our physiotherapy colleagues can identify those patients who need to receive physiotherapy. To achieve real-time dashboards of these clinical indicators, we must provide appropriate information technology systems so that we can embed the routine and systematic collection of data into our day-to-day processes to capture data as a side-effect of our direct care, and not as an afterthought once care has been provided.

So what is the answer?

We need to be ambitious and demand systems that enable intelligent and prudent healthcare. We need to start with understanding our problems, and design our clinical information systems to solve those problems. As clinicians, we need to take ownership of the data on our patients and make data collection routine.

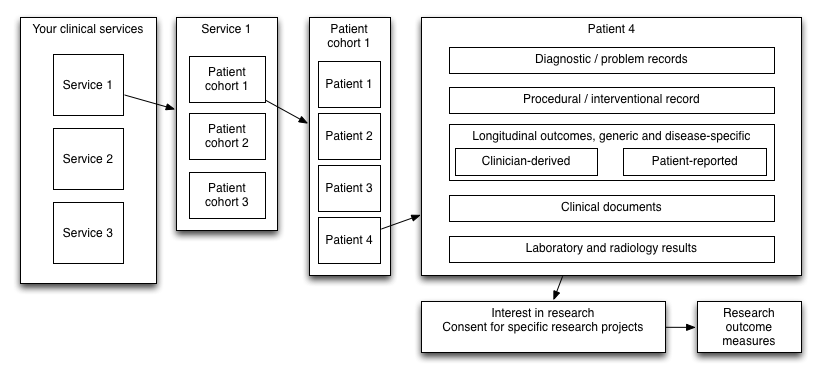

Importantly, taking a domain-driven approach to solving clinical information system design results in boiling down most of our data problems into two broad categories:

- Cohorts

- Outcomes

A cohort is a group of patients who share a defining characteristic, such as the same diagnosis, symptom, clinical finding, or receipt of the same procedure or treatment. I have written about the importance of defining cohorts previously and will not duplicate that post here except to say that SNOMED-CT, a comprehensive and modern terminology provides a hierarchical ontology. As a result, we can record that a patient has “Addison’s disease” (concept identifier 363732003) and determine algorithmically, by virtue of the ontology, that the patient has a type of “hypoadrenalism” (concept identifier 111563005). As such, we can then potentially identify all patients with hypoadrenalism even if they have been recorded as having “Addison’s disease”.b

Value-based healthcare is predicated upon understanding and improving our patients’ health outcomes. As such, the systematic and routine collection of outcomes must underpin everything we do; what point in doing a hip replacement if we do not assess how our patient fares? Outcome data may be recorded by health professionals, but the most important outcomes are those that address the needs of our patients and as a result, patient-reported outcomes are critical in understanding how to configure and how to monitor our clinical services. In addition, there are other techniques that provide compelling real-world measures of outcome such as return to employment, need for care, long-term dependency and frequency of complications which should be combined with our other data in order to build well-rounded, comprehensive longitudinal measures of outcomes.

Importantly, these two broad categories are mutually dependent. How can we interpret quality of life information without an understanding of the patient characteristics?

As such, SNOMED-CT permits us to understand our cohorts and partially allows us to record patient outcomes, but we must supplement SNOMED-CT with the routine collection of outcome data by professionals and by patients using a variety of disease/procedure and generic outcome tools.

Routine collection of data

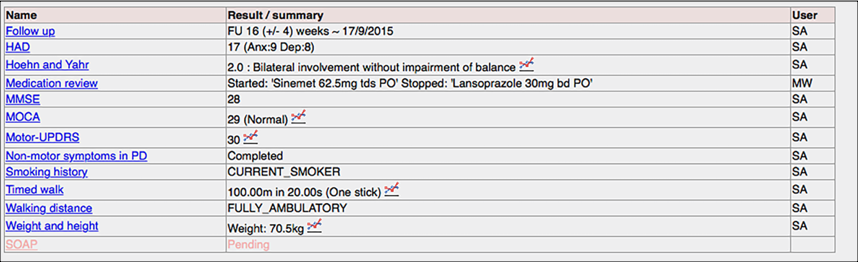

So how can we build the right tools for health professionals and patients to allow the routine and systematic collection of data to support our cohorts and monitor our outcomes? Well, I’ve been trying to do this since 2009….

Here is an example of recording diagnoses:

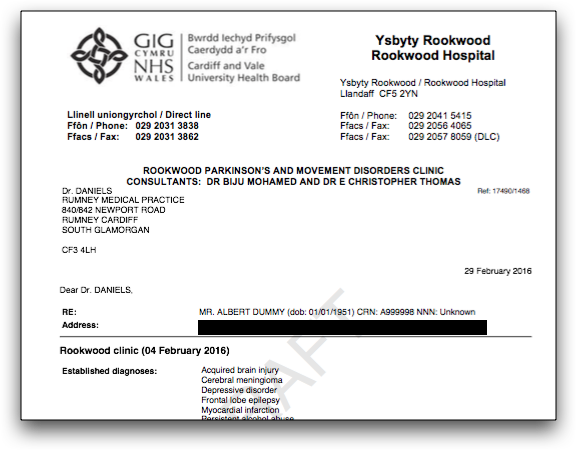

Here we routinely record the toxin, dose and site of injections for our botulinum toxin clinic. It saves time for the clinician, because we can then generate the letter to the general practitioner automatically.

Behind the scenes, each click records data as a SNOMED-CT coded procedure and site and drug.

And here, my iPad application collects patient reported outcome measures in the clinic and makes them immediately available to the clinician:

How can do this at scale?

Importantly, my software records highly structured data using SNOMED-CT and an open information model. As such, documents created using the system consist of a binary blob of data representing a PDF representation as well as a computer-readable data structure recording diagnoses, problems, procedures and interventions in a standardised way. The problem is that, presently, while I expose these data, there are no other applications running in the live clinical environment that are able to interact, yet.

We need to collect these data across all of our organisations and services:

As such, we must stop thinking at the scale of individual services, diseases and organisations and instead recognise that we must support interoperability between multiple disparate clinical information systems across enterprises. This requires action to define appropriate data standards and data exchange, with the adoption of terminology such as SNOMED-CT and LOINC, the use of defined information models such as HL7 FHIR and openEHR.

Such standards must be mandated for new developments to avoid vendor lock-in, and ideally we should be building vendor-neutral archives of data that other applications, whether in-house or from third-parties, can use for data persistence and retrieval.

The design of clinical systems must begin with the patient and support the provision of their care irrespective of whether they begin their journey in one organisation and continue it in another. Similarly, we need to train a cadre of experts in health informatics in order to ensure that the routine use of open, standards-backed interoperable information for healthcare is given priority in system development instead of a traditional focus on information for the management of an individual organisation.

Most importantly, if you are a health professional, you must start to demand more information technology in order to support your day-to-day work looking after patients. You need systems to allow the rapid and routine collection of structured data and to be given the required tools in order to make sense of those data for your patient and your services with data linkage and realtime clinical dashboards for your services, your cohorts and your outcomes.

Footnotes

a: The telephone was patented in 1876.

b: I have turned the usual use of SNOMED-CT upside-down as a simple demonstration of using the ontology to derive semantic understanding in a recent blog post.