Communication is key

At least I’m consistent. I wrote this in a rapid response in the BMJ 14 years ago:

Dear Sir,

It is important to note that of the ten points raised, seven directly relate to the communication of data between professionals and organisations. This is no surprise; when a casenote is reviewed it is entirely composed of communications. It is here that information technology has its greatest benefit.

The NHS needs to create open, extensible standards for the communications that make up a patients notes. Creating huge centralised systems that meet today’s needs temporarily and adopt a “one size fits all” will lead to NHS IT yet again mimicking past IT disasters, such as the scrapped benefit cards payment system, the new air traffic control centre at Swanwick and the national insurance recording system.

Once national standards in messaging, authentication and authorisation are created, individual system suppliers can connect their disparate software, new and legacy data to create a seamles integrated electronic patient record, that can slowly evolve, develop and keep pace with developments - both in IT and medicine. It is important not to forget the legacy data that is out there - in pathology, and even in radiology. Bespoke radiology imaging software should be able to publish patient’s data in a standard fashion allowing it to be integrated at the desktop.

Local systems can be designed with local users in mind, all operating on the same secure network. When a local rapid access endoscopy unit wants to start prospectively auditing requests, customising their own request “messages” should be straightforward and seamless to those that use them.

In creating a working, living, evolving distributed electronic patient record, it does not matter that data is stored by a number of different organisations, and it does not matter when in fifteen years time the NHS organisational landscape changes. Centralising data away from the people who create it would be a mistake. A distributed flexible system is easy to centralise in the future when needs change. The converse is not true.

The recent Welsh publication “Informing healthcare” [1] talks about created a Wales-wide electronic patient record. It goes on to ask whether Welsh systems should be aligned to information standards in their English counterparts. I find it difficult to believe that such a question even needs to be asked, and it is this lack of far-sightedness that means the millions of pounds will yet again be squandered on IT systems that its users can’t use.

[1] “Informing Healthcare”. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/ihc

The fact that most medical records are a type of communication is important. It is easy to assume that medical records are simply a record of medical practice, a longitudinal narrative of what happened to a patient. They are not. Medical records are a key enabler of healthcare. They are a piece of the workflow, a way of formulating and synthesising evidence and of marshalling opinion.

When medical records are on paper, they are familiar and useful but have their own share of problems as well, as I discuss in Section 2.1 of my clinical design document. Their sheer weight gives me information about the burden of pathology or at least, medical care in or for an individual patient.

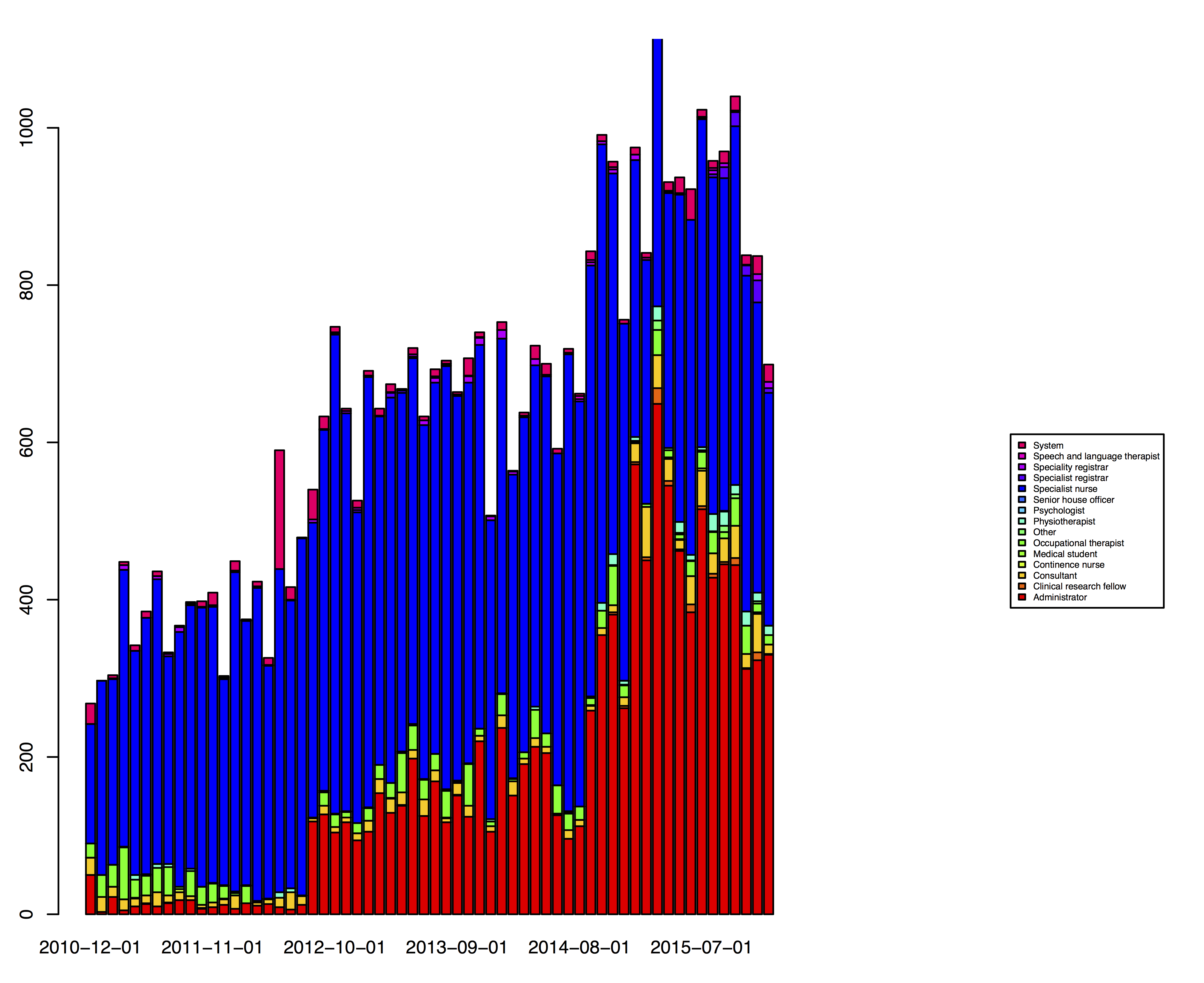

Digitising the medical record is much more than simply copying the workflows and processes around paper records. When I added secure messaging to the PatientCare platform back in 2009, the teams looking after patients with a range of long-term health conditions embraced the ability to send messages linked securely to an electronic patient record with enthusiasm. They now record over 1000 messages every month; the graph below shows the adoption rate between 2010 and 2015.

However, users soon asked for “carbon copy” functionality, asking to send a single message to multiple colleagues. I have still not heard a compelling justification to add this and have not done so. Users use messaging not just as a means of communication, but just as on paper, as a means of managing their work, the tasks to which they must attend. Conceptually therefore, a message written on a post-it note and put on my desk acts not only as a means of communicating something, but is usually asking me to do something. In digitising this process, it is not appropriate to simply create a new form of electronic mail, but understand how paper is not just a form of communication.

The commonest reason cited by users wanting a “carbon copy” function was to “let someone know” something. I would ask why this were needed, unless that person had to act on that information. If that indeed were necessary, then the user should forward the original message with an annotation. Otherwise, the message is clearly visible for all time within our electronic record and so would be visible to the person who “needed to know but not do anything about it”, when they did need to see it.

Was I therefore wrong in 2003 when I said that “communication is the key”. I don’t think so: I was trying to push for interoperability and data standards, but medical records are much more than clinical correspondence and so digitisation must model not only the communication but the processes and workflow in which that communication sits.

My final thought: medical records are all about people: the patient obviously, but also the team of health professionals who work to look after and support that patient. Digitisation of medical records that neglects either communication or the people involved will, in my opinion, be doomed to failure.