Pluripotent data: A data strategy in health and care

Pluripotent data

Pluripotent: capable of giving rise to several different cell types.

“Pluripotent” is a biological term applied to cells that are undifferentiated and are capable of differentiating into several different cell types, and therefore satisfy a variety of demands

Therefore, I propose the term ‘pluripotent data’ for use in healthcare.

In essence, I use ‘pluripotent data’ as a way of describing the prioritisation of data harmonisation and standardisation through common data models that may be used, directly or indirectly, for multiple purposes to meet a variety of demands.

Principles supporting a data strategy

The key principles that should underpin a healthcare organisation’s data strategy are:

- Vendor neutrality

- Use of standards

- Harmonisation, intermediary structures & multi-purpose analytics; pluripotent data

- Specialty extensions, registries and research

- Governance and transparency

- Procurement, compliance and audit

- Training and education

Vendor-neutrality

The current situation is that healthcare data varies between organisations and across applications and depends on purpose. Health and care data can be used for multiple purposes such as direct care, reporting, research, service management and quality improvement.

In the main, the current fragmentation reflects organisational and governance structures - this is Conway’s Law in action.

“Any organisation that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.” Mel Conway

The consequence of this ‘Law’ if that if direct care, hospital administration, quality improvement and research are separate in an organisation, or represented by different organisations, then the ‘systems’ developed will mirror the pattern.

No wonder then that end-users feel such significant fragmentation. This is not a new issue.

The various clinical systems, many of them paper based, differed from one another and had no relationship with the administrative hospital-wide systems. The funding made available in the late 1980s and early 1990s for medical and later clinical audit helped to reinforce this separation by making available to groups of clinicians money for small local computer systems. The lack of any connection between these different systems, one administrative, the others clinical, for collecting data cannot be explained solely on the basis of some technical or technological reason. It was just as strongly a reflection of a mindset that clinical matters were the sole domain of clinicians and non-clinical matters, to do with the management of resources and with the movement of patients into and through the hospital, were the preserve of managers and administrators.

Bristol Heart Enquiry, 2001. See Using data for patient safety

The key thing to remember about Conways Law is that the modular decomposition of a system and the decomposition of the development organization must be done together.

Martin Fowler Conway’s Law

The term ‘Inverse Conway Maneuvre’ (also known as ‘Reverse Conway Maneuvre’) was coined by Jonhy Leroy and Matt Simons (ThoughtWorks) in December 2010.

In what could be termed an “inverse Conway maneuver,” you may want to begin by breaking down silos that constrain the team’s ability to collaborate effectively.

Martin Fowler

While there are valid criticisms of the ‘Inverse Conway Manoevre’ relating to organisational change, it can inform our approach to data and data flow.

In essence, rather than framing data in terms of applications, we instead focus on data. Our data is therefore vendor-neutral.

And an ‘Inverse Conway Manoevre’ looks to set up collaborative efforts than span organisational and domain boundaries so that we build a common data model that can, either directly or indirectly, be used for multiple purposes.

In Wales, through the Welsh Technical Standards Board (which I chair) and Welsh Government, we have mandated HL7 FHIR as a foundational standard for operational clinical systems. This is an important step to build interoperability between different clinical systems and fosters the re-use and composition of data.

However, HL7 FHIR does not solve semantic interoperability unless one builds in mechanisms to ensure that the information standards - the dictionaries encoding different types of information such as reference data like location, or staff member, or patient, or value sets - are aligned.

As such, we need to be explicit in mandating the FAIR principles, so that data are:

- Findable (through metadata and linked data technologies)

- Accessible

- Interoperable (through standards and vocabularies and collaboration)

- Re-usable (through provenance and standards)

Data harmonisation

There is sometimes a tension between what we think of as general purpose healthcare data and specific demands. For example, we contribute to a national audit on stroke care, but because we have separate clinical and dministrative systems and this national audit, we have to have dedicated members of staff keying in information from multiple sources manually in order to satisfy the specific demands of this (important and useful) national audit.

Instead, we need a mechanism that provides a defined patient-centric common data model (CDM) that acts as a foundation that can be extended to suit multiple purposes. This means that, for example, two organisations can generate combined regional datasets simply by composing (merging) their data.

This highlights two important requirements:

- We need to think of our extract/transform/load (ETL) operations as first-class and important

- We need to recognise the value of shared tools and knowledge in the process of data harmonisation across health and care.

For example, Welsh Government are keen to modernise the dataset in relation to outpatients. Until COVID, an outpatient encounter was not counted unless the appointment was face-to-face, despite many clinical services offering telephone consultations for many years. In essence, they want greater detail on scheduled outpatient care and include information relating to procedures and problems/diagnoses.

The problem is that, at the time of writing, they cannot cope with such information encoded using SNOMED CT and instead want categorical data - “just one of the top five categories”. This is fine for central reporting, but the team suggested a clinical-facing application that would capture those categories at the point of care.

This is quite wrong.

Do we accept that demands for central data reporting define our clinical systems?

Certainly not.

So we must instead recognise the importance of our data infrastructure and ability to map, process and convert structured meaningful data for a variety of different purposes.

It also emphasises how important it is that such decisions are made by people with required technical knowledge: we need to also consider the digital and data capabilities of our health and care workforce.

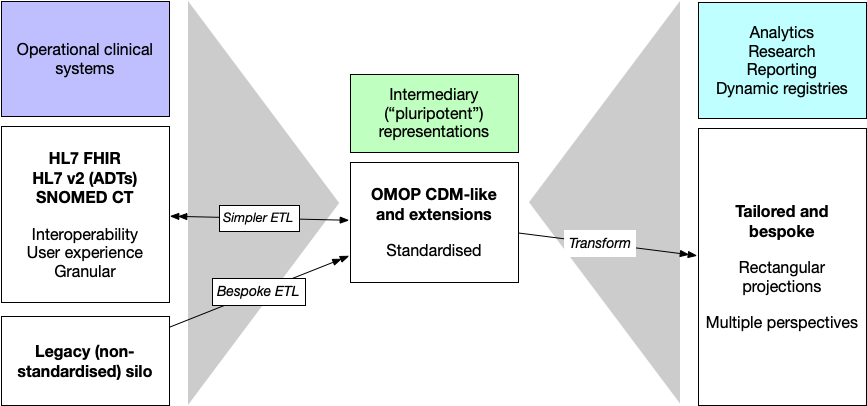

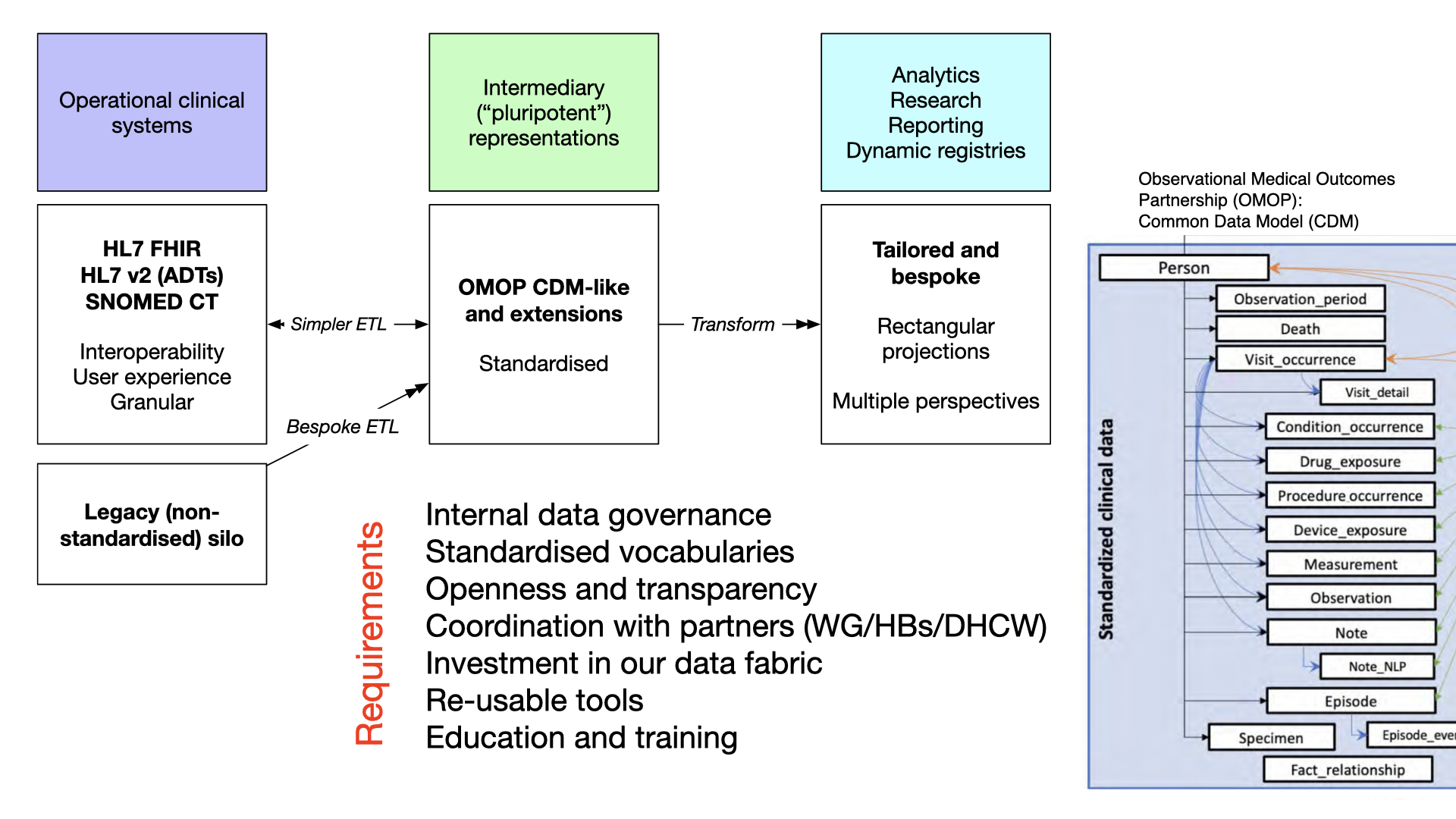

Using intermediary ‘pluripotent’ data representations

In this diagram we have multiple operational clinical systems and a variety of methods of extract and transform to our intermediary patient-centric data representation. The OMOP CDM is a good example of such a representation, potentially being useful for solving multiple demands, and sufficient flexibility to be specialised easily.

From such a CDM, we can subsequently build further data pipelines permitting more bespoke ‘rectangular’ projections of our granular and complex health data suitable for reporting requirements or demands of centralised registries.

In this, we gain multiple perspectives, or prisms, on the same common data models.

You can read more about OMOP and their common data model here.

Requirements

A data strategy with common data models at its heart has important technical, organisational and cultural requirements:

- Strong internal governance

- Registration and monitoring of data flows (information governance, feral apps, o365)

- Standardisation of data across uses

- Harmonisation

- Understand common foundations

- Maintenance and publication of common data model

- Dependent on appropriate governance e.g., local clinical and technical design authorities (and their links with others)

- Standardised vocabularies

- Essential for semantic interoperability

- Match to regional, national and international standards

- First-class mapping and transformation

- To satisfy myriad potential requirements - operational clinical systems, analytics, reporting and research

- Openness and transparency

- Radical transparency and visibility; working in the open

- Publication of standards used, for all purposes. Openly available and managed and updated

- Versioning and registration of use

- Avoid breaking changes; additive change: you don’t care if your delivery truck bringing your parcel also has other parcels on it.

- Coordination with partners (e.g. WG/HBs/DHCW)

- We must work across region, across Wales and across UK

- Our collaborative efforts must be prioritised and supported

- Some of what we need can and should be delivered by our partners

- Investment in our data fabric

- Raise the visibility of our data infrastructure

- Balance short-term delivery goals with longer-term standardisation, harmonisation and documentation

- Avoiding technical debt and ‘big ball of mud’ architectures; Infrastructure on demand and as infrastructure as code. Declarative.

- Focus on interoperability, principled approach based on re-use, understand commonalities/foundational data structures

- Re-usable tools

- Investment in tooling, and pipelines, that are ‘invisible’ and yet vital. “Our plumbing”

- Investment in our ability to extract, transform and load data; “internal interoperability”

- Could and should be shared across Wales

- Open standards, and open-source at foundations

- Education and training

- Health and social care

- Regional partnerships

- Inculcate art-of-the-possible, data skills, across organisations

- Workshops, investment in training, workforce and digital skills, peer support

There are common themes across these requirements mainly in relation to prioritising, investing in, collaborating and governing in relation to data.

I’d be interested in your feedback. What else have I missed? What should be in the data strategy for Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, or for any healthcare organisation for that matter?

Working in the open is important. Let me hear your views. Email, or raise an issue on https://github.com/cavdigital/digitalstrategy2023/issues.

Mark