Healthcare and technology

This blog post is about digital transformation in health and care.

Firstly, I discuss our aspirations to create a seamless patient-centred service that blurs the boundaries between disciplines and organisations and how technology is an enabler of those ambitions.

Secondly, I discuss the paradox that while the best way to build that seamless service is with technology, that technology should itself be highly modular, fragmented, and developed and continuously improved using an agile, responsive, adaptive approach that uses real-life fast feedback and a continuous learning culture. Modularisation permits rapid deployment and iteration in parallel.

Thirdly, I discuss the importance of an overarching set of broad principles, adoption of open technical standards, openness and transparency to set strategic direction (“this is where we want to go”) while at the same time creating smaller, semi-independent teams trusted, and empowered, to take the incremental steps to get us closer to our intended destination.

As such, I reinforce the need to think carefully about how we structure our technical architecture and governance to start that journey - accepting that we will need to adapt and change our approach as we learn how to deliver health and care technology in a different way to that used previously.

Let me know what you think.

Transforming health and care: creating a seamless service

Digital technology is going to transform healthcare.

“We’re at the beginning of the digital revolution”

by Bill Gates in his foreword to Satya Nadella’s book “Hit Refresh”, published not, as you might initially guess, twenty years ago, but in 2017.

Health and care organisations, and those in charge of running health care systems, such as those within the National Health Services in the UK, need to understand that it is no longer appropriate to treat information technology as something separate from their core business.

“The BMW Group’s CEO that said in the future the BMW Group expected more than half its R&D staff to be software developers.”

Edward Taylor and Ilona Wissenbach, “Exclusive—At 100, BMW Sees Radical New Future in World of Driverless Cars,” Reuters, March 3, 2016.

We see that in many industries - and that’s not only because of modern innovations such as mobile devices, machine learning and our ability to process enormous sets of data, but simply because information technology is the best way to deliver the results that we want: a seamless, responsive, patient-centred, evidence-based healthcare system that, at its heart, is driven by patients and professionals working together; collaboration, communication and a data-driven approach to building health and care services.

In essence, our goal must be to achieve a seamless, responsive, patient-centred “one system” healthcare service within NHS Wales, and technology is critical in enabling that. We need to break down silos between disciplines and organisations and draw together the common strands of work that underpin care for an individual patient while also caring for populations of patients and enabling better service design, supporting ongoing continuous improvement and transforming clinical research.

It should be no surprise to see that a seamless “one system” outcome is explicit in the new NHS Wales health and care strategy: A Healthier Wales.

But we have have to ask a question: what is the right approach to delivering technology for health and care to deliver that seamless service?

One option is to think that we can use top-down centrally-driven diktat to build a single solution for our “single” service and impose that solution on our services, but is that the right way to deliver software in health and care?

The software value chain: delivering what we need

Health and care needs software delivery at scale.

We need to become much much better at developing, deploying and constantly evaluating and improving software, because software is critical to what we need to do improve our health and care system.

The problem is not with our organizations realizing that they need to transform; the problem is that organizations are using managerial frameworks and infrastructure models from past revolutions to manage their businesses in this one.

Kersten, Mik. Project to Product . IT Revolution Press. Kindle Edition.

Health and care needs to learn how to deliver software : reliably, safely, reproducibly, at scale and to ensure ongoing monitoring, evaluation and continuous improvement.

But there is a paradox. We know that the worst ways to create a seamless “one system” approach are thinking we can build a single monolithic application or expect the procurement of a “system” to solve, for example, closer working and communication between health and social care.

The best way to slow down delivery is to have an approach to technical architecture and wider governance structures that slows down the software value chain. The key to software delivery is delivery, and yet some organisations treat software as if they were managing capital projects such as building a new road or a bridge. In most cases, the technology is the easy bit; its the implementation on the ground across multiple complex adaptive systems that is most difficult. But we also need a design that makes it easy and safe to change.

People who think building technology is difficult and complex tend to want to centralise and control its development, because that feels less risky, but that approach is wrong.

With the advent of readily-available frameworks, rapid application development tools and drag-and-drop user interface design, building software is actually quite easy! What is hard is integration and deployment - the actual implementation of technology to support the transformation of health and care services.

So the best ways to speed up delivery of valuable technology are

a) to become agile, b) break up our software architecture into smaller, easier-to-manage products and, c) create strong leadership to ensure a cohesive credible strategic approach.

Agility means recognising the benefits of adaptability, flexibility and fast feedback. Health and care need to learn from other industries who are adopting these practices with pace, and improving the safety and reliability of their software delivery pipeline.

Modularisation and unbundling of services means that they can be developed independently, in parallel, with agreed technical standards defining their interactions.

But just because we have multiple modules all being built, deployed and continuously improved independently, it doesn’t mean that each doesn’t form a cog in the wider single system. By single system, we should mean a credible, coherent, overall high-level strategic approach means that there are clear principles that guide all of our work, with definite and explicit direction-of-travel, but empowered teams delivering the incremental steps on that, truly collaborative, journey. That means a shared vision, but small steps, and that doesn’t mean only for our technology products but in our overall approach to management and leadership.

To succeed, a team must be a real working group with proper time to devote to change, rather than a ‘steering committee’ who meet once a quarter for lunch. The team will achieve little if the ‘Agile’ element is merely added on top of their existing jobs. Proper time and space must be devoted to this, which means freeing individuals from existing commitments.

Seven steps to building an agile organisation , checked on 18/9/2019.

Many of our decisions are nuanced and a balance of positives and negatives, not unlike the practise of medicine itself, and such decisions must surely balance a range of factors including existing investments, cost, value, opportunity cost of not delivering valuable software. As such, we need to also focus on openness and transparency and that means clearly articulating the decisions that need to be made, how we are going to approach them, and finally the delicate balancing act that weighs up those factors. One important principle of agility is to make smaller, incremental decisions so that we lower risk and create greater opportunities to learn.

What does this mean for Wales?

“Admitting that we don’t know, leads to a better outcome” War and Peace and IT by Mark Schwartz

“Incremental releases for bigger changes” from Making Safe and Frequent Improvements to the UK Passport Service

“Our work can be used to engender culture change, and inculcate a respect for the appropriate use of technical standards across health and care in Wales. “ from my blog post for the Welsh Technical Standards Board (WTSB)

We have so many amazing individuals and teams across health and care in Wales, and so much drive to continuously improve and transform services. Our work, across health and care in Wales, should be one to provide a toolbox of computing and data services that can be used to support the transformation of how we work, collaboratively.

Personally, I don’t really care what patient administrative system an organisation uses; I’m far more interested in the articulation of the outcomes we want, and a balanced decision as to the best way to achieve those outcomes with some broad principles to provide consistency on that weighing up procedure, together with what information goes in and what information comes out.

After all, we have seen different PAS replaced with a “national PAS” in different organisations in Wales, but each has been configured differently and we still have no easy way of tracking pathways for patients across organisations, and any clear consistency on how specialities are coded. Likewise, I have used a “national application” to view a patient and found out that patient is alive when I’m sitting in one clinic, and dead in another.

It’s easy to see how we’d reach agreement on high-level outcomes - what I do care about for PAS is that we have a single patient record, that record is accurate and up-to-date, and that I can track pathways of care across organisational boundaries; once we agree the desired outcomes within a specific domain, we can apply our broad principles to start to tackle those needs by standardising our contracts between software components, without necessarily having to standardise the components themselves.

Strategic, flexible programmes but specific products and small, long-lived teams

One of our goals is to generate a credible and cohesive strategy to deliver valuable software for our teams across health and care in Wales. I’m interested in finding the natural fault lines in our overall work to create strategic programmes that can work semi-independently from others, and so minimise the need for constant checks and approvals from advisory groups, boards and stakeholders. Such an approach minimises dependencies and the lessens the need for constant coordination. Good governance is essential, but good governance is also streamlined and efficient governance.

It is seductive to think about programmes of work delineated by specialty, service or organisation. That approach leads to programmes such as a “National imaging programme board”, who has led on procurement of a new Picture Archive Communication System (PACS) for radiology.

However, it is probably better to think of programmes of work aligned to strategic themes instead - orientated to the outcomes we want, so that there is alignment and cohesiveness, when possible. For example, it is possible that an imaging programme board might recommend procurement of electronic test requesting functionality at the same time as laboratory colleagues procure the same functionality for laboratory tests. If these programmes are not aligned, and occur independently, test requesting will not feel cohesive for end-users.

One option is to ensure that all stakeholders for all programmes all talk to one another, but that results in an exponential need for cross-talk and slow, difficult decision-making because all programmes of work are dependent on one another. Instead, programmes of work should be aligned strategically in core domains aligned to operational outcomes, planning to minimise cross-dependencies and coordination, and explicitly recognising common needs and adopting a platform approach to common national services.

For example, it might well be best to procure separate electronic test requesting functionality to get early benefits, so that professionals and patients get functionality delivered quickly, but strategically, ensure that both radiology and laboratory procurements provide standards-based APIs so that a concierge service can be built to streamline workflow for end-users. It is almost certainly wrong to jump to a decision on this today, as it may be that electronic test requesting is provided at no cost bundled with a laboratory management system, for example: our goal surely is to build capacity for empowered teams to make these kinds of decisions because they will be the experts?

Recognising that we don’t have all of the answers is absolutely essential, but that doesn’t stop us taking responsibility for the broad over-arching principles and guard-rails that define our overall mission. I’m pretty sure that we will have to adapt and modify our plans as we go along, and be open and transparent about how we discover hitherto unconsidered challenges and how we will learn to overcome them.

In keeping with an agile ethos, the best way to really understand how health and care in Wales can benefit from this approach is to try it with small experiments and get fast feedback.

We don’t need to have a big-bang approach to transformation, or indeed, plan massive re-organisation.

Instead, what can we do now to prove the effectiveness of this approach?

Next steps

I’d prioritise three programmes of work in order to a) create early benefit, and b) learn whether this approach can work in health and care, identifying unforeseen challenges and refining our approach:

- Demographics programme

- Appointments and scheduling programme

- API management/authentication/authorisation logging.

Demographics are an essential core requirement for a single patient record, and this programme might focus on coordinating the following products:

- A HL7 FHIR based canonical demographic application programming interface (API)

- A legacy HL7v2 pull/push demographic update messaging service (for legacy applications)

- Enterprise master patient index

- Patient administrative systems (PAS) - ie subsuming demographics user group and working with health boards to harmonise our understanding/processing of demographic data.

Likewise, appointments and scheduling are a vital foundational service and the data and computing services underpin several important products such as professional-facing applications like a national portal as well as patient-facing portals and applications. In addition, our work on single cancer pathway and outcomes relies on an understanding of patient’s interactions across the health service, such as appointments in multiple hospitals and in different departments such as radiology.

It’s already clear that appointments and scheduling have a dependency on demographics - we need to track a patient across organisations irrespective of their local identifiers. We can contractually define the dependency between these two programmes so that our appointments and scheduling programme can simply rely on an abstract computing service that manages the complexity and edge-cases inherent in demographic matching.

The appointments and scheduling strategic programme might initially include the following products:

- A HL7 FHIR based unified appointments and scheduling view across multiple organisations and departments

- An analytics product that streams and stores (warehouse) appointment and scheduling information to permit analytics and real-time dashboards of service use

- A patient-facing portal to provide a simple view of upcoming appointments, with an initial concierge service to provide functionality to change appointments (this could be managed by humans initially and yet still provide valuable functionality for citizens).

- Integration with commercial off-the-shelf patient portals, such as the “Patients Know Best” portal in pilot in Swansea Bay and Cardiff & Vale, so that appointments are visible to patients using these products.

It could include work to look at how we might manage to provide similar functionality for healthcare services for NHS Wales citizens whose care involves crossing over into NHS England, reinforcing the need to adopt open technical standards and work in partnership with external stakeholders. I’ve sketched out a more detailed “Appointments and scheduling” programme here

One key aspect to this approach is a flexible, prioritised and adaptive approach to deciding on the structure of programmes, but software delivery made up of small, focused, and long-lived cross-functional developer teams.

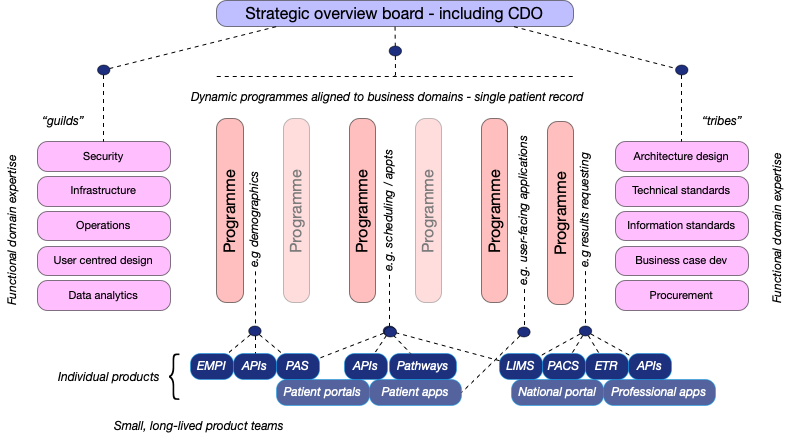

I’ve tried to show this in the following schematic, but this is simply a broad-brush, illustrative approach and not a fixed, regimented plan.

Here we see “guilds” or “tribes”, with specialist expertise in specific vertical domains such as security, engineering, and design, advising and being brought together into specific small teams to deliver specific products, such as an API for demographic data that are governed and coordinated, at least initially, by a strategic programme, because at the moment, we are starting from a fragmented and incoherent set of national and local systems, services and applications. Over time, our strategic programmes can and must evolve to meet the ever changing challenges we face, while our product teams continue to work to deliver valuable software components.

In fact, we might recognise three different categories of small, long-lived team that will be needed as we mature in our approach in health and care:

- A value-stream aligned team type - focused on solving problems by understanding and then delivering software for end-users. This might be a team responsible for building a patient-facing application.

- An enabling team type - a “squad” - focused on supporting product teams in specific technical domains - in other words, a technical consulting team that works across product teams to empower and up-skill, in a collaborative way. For example, I understand that this is how Google’s Site Reliability Engineers (SRE) work. Such teams might extend their work across other public sector services.

- A platform team type - focused on building core, common data and computing services that underpin delivering applications to end-users, often hiding underlying complexity or specialisms by providing an easy-to-use self-service API.

This is an approach similar to that outlined in Team Topologies by Matthew Skelton, and indeed, we can see that it is likely that, over time, platform services will become increasingly more complex, and leverage other platform services as our demands and expectations rise.

Most of our work here is in building capability - capability to adapt to change and deliver at pace.

Governance that follows architecture

Implicit in this approach is recognition that our technical architecture and governance must go hand-in-hand. As we know:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

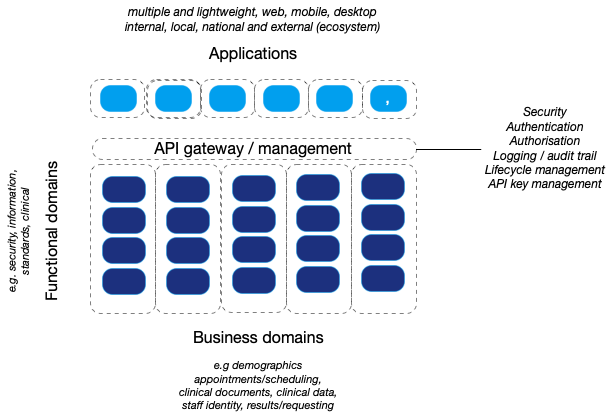

That means recognising that a modern, health and care enterprise architecture might look something like this:

In which there is loose-coupling between modular components providing software and data services, orientated and aligned with important strategic business (operational) domains. We will move towards lightweight applications that are focused on creating delightful user-centred workflows, that leverage platform services for business logic and data services.

Let me know what you think.

Mark