The importance of cohorts... and SNOMED-CT

A cohort is a group of patients who share a defining characteristic.

In clinical research, researchers recruit a group of patients with a specific disease or a specific problem or who have received a specific intervention and then might monitor their progress in an observational study or monitor the effect on an intervention in an interventional study.

In such studies, there is a systematic and dedicated collection of research data, usually to a high-standard using a pre-prepared schedule to avoid bias and to ensure that the appropriate data are acquired.

One would think that it would be the same in routine healthcare but it is not. Most information is recorded as unstructured free-text and data collected are primarily used for administrative and managerial purposes. As I wrote in my domain-driven clinical design document, “As a result, we commonly know how many patients are seen in clinic, but have very little information as to why they are being seen or how they fare after treatment. Important questions such as ‘how many patients with Parkin-son’s disease do we care for?’, ‘what are the outcomes for patients after having a mastectomy?’ or ‘why are we seeing these patients in outpatient clinic?’ cannot be answered.”

In fact, it is not just understanding and assessing our services and outcomes that require this information, but new technologies such as real-time analytics, algorithmic support and artificial intelligence needs prospectively-captured data recorded at the point–of-care.

Some might point to “Hospital Episode Statistics” (HES) data as a way of understanding our patients but these data are woefully incomplete and inaccurate, do not usually include outpatient episodes of care with diagnostic entities recorded using a classification system (ICD-10) rather than a clinical terminology.

The logical answer is to encourage the routine and systematic collection of structured data by clinicians for clinicians.

SNOMED-CT

SNOMED-CT is a large, modern and comprehensive terminology. In the above video, you can see me entering clinical diagnostic terms quickly and having them mapped to SNOMED-CT concepts in real-time. These concepts exist within a large and complex hierarchy of relationships which give algorithmic understanding. I use this in an electronic patient record system to identify patients with motor neurone disease; it will identify patients coded with a diagnosis of “progressive bulbar palsy” but the SNOMED-CT hierarchy can be navigated to work out algorithmically that this is a type of motor neurone disease.

I have explained more about SNOMED-CT in Section 4.1 of my domain-driven clinical design document and I have a paper in print in the Future Hospital Journal which should be published in the next issue.

SNOMED-CT isn’t limited to diagnostic concepts but includes terms for all range of concepts such as countries of birth, ethnic origins, procedures, medications, devices and even occupations. In addition, there are cross-maps which facilitate the mapping of a concept to and from other classification and terminology systems such as ICD-10 and OPCS.

Here is an example of entering SNOMED-CT terms for medications:

The importance of implementation

I have not been able to identify a working SNOMED-CT implementation in the UK before 2009, which means that, as far as I know, I actually had the first working system in clinical practice in the UK deployed in October 2009.

I think there are five main issues when it comes to implementing SNOMED-CT:

1. You need to make it fast.

If you have a look at the SNOMED International provided browser, you can navigate the SNOMED-CT hierarchy and get a feel for how it is structured. However, you will notice that search is very slow. While its size makes it comprehensive, it is technically challenging to implement in an effective way. It is possible to do so however as you can see from the screen recordings above.

2. Terminology shouldn’t be a bolt-in, but the lingua franca in your data models and your software.

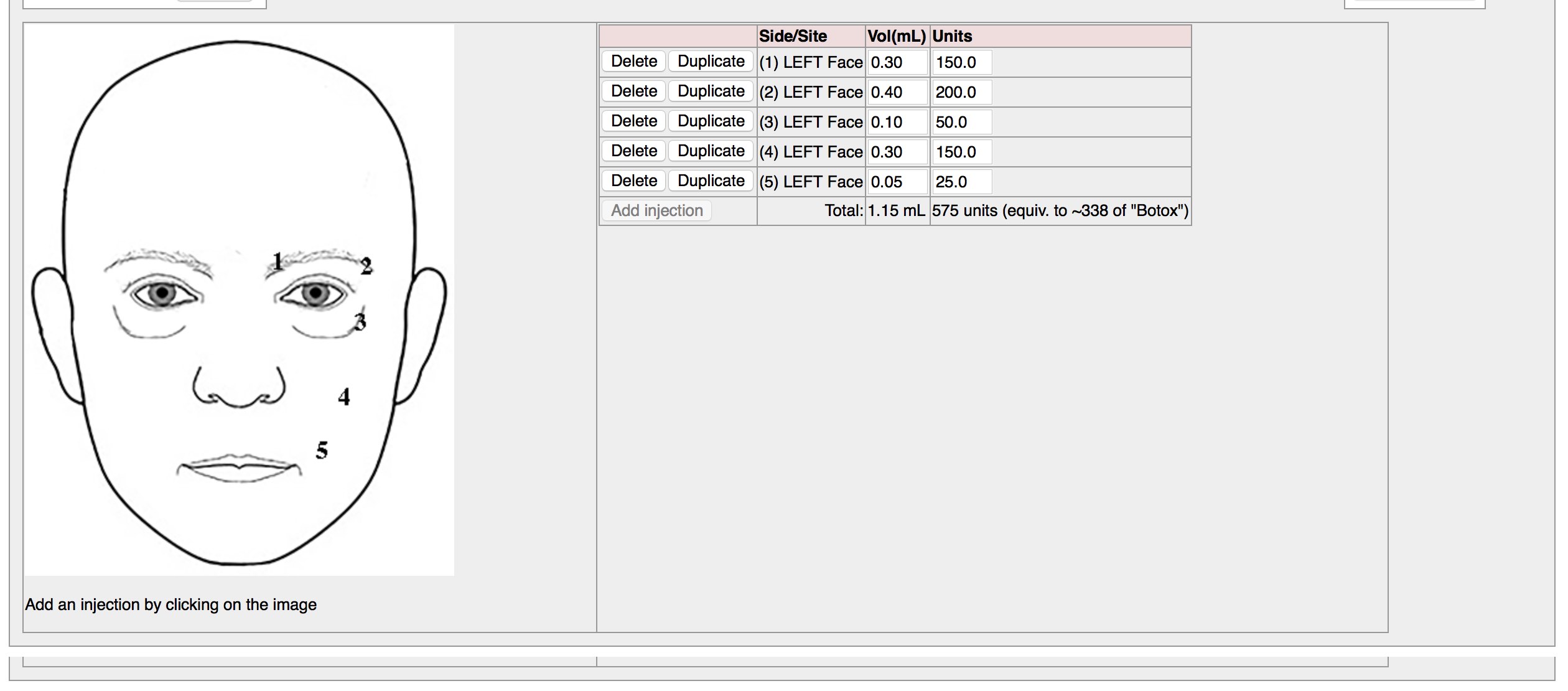

SNOMED-CT data entry does not need to only occur by allowing your users to search for a specific term. In my homegrown EPR, choosing locations on the face when recording botulinum toxin injections enters SNOMED-CT terms behind the scenes at the data level.

3. It’s not just about data entry.

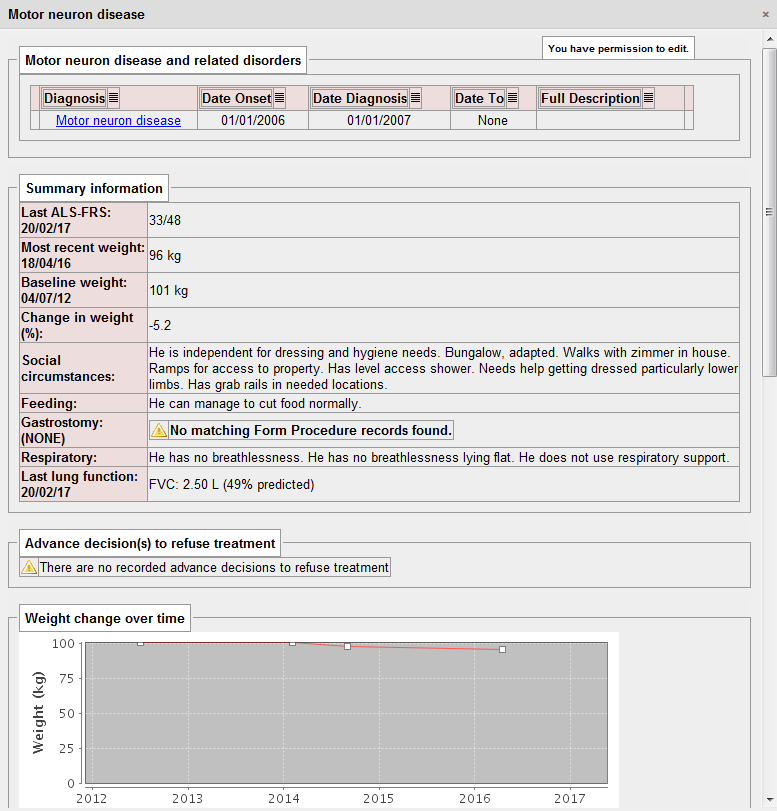

If your terminology system is a bolt-on, then it is difficult to do anything clever with the data in real-time in order to support clinical care. If however you use SNOMED-CT to enable real-time analytics, then you can switch functionality on and off depending on clinical context. Here we analyse the patient record to generate a motor neurone disease summary and look for records of gastrostomy insertion simply by querying the patient’s data leveraging the semantic understanding that SNOMED-CT provides.

4. Don’t start thinking about subsets

There have been many working groups set up by different specialties to try to organise and curate subsets, limited lists of concepts from within SNOMED-CT and I strongly believe that this work is a waste of time.

Instead, those people should be focused on improving SNOMED-CT as a whole, reviewing and deprecating concepts and ensuring that the concepts that are found in modern clinical practice are represented adequately.

I believe that subsets have arisen due to fundamental shortcomings in the implementation of SNOMED-CT and I haven’t found a need that subsumption can’t solve by itself. Subsumption refers to the hierarchy of SNOMED-CT concepts that arises from IS-A relationships in that, “progressive bulbar palsy” IS-A type “motor neurone disease” or “bronchopneumonia” IS-A type of “respiratory disease”.

Subsumption means that a decent implementation (and mine is one of them - see it at https://github.com/wardle/rsterminology) can use those relationships to limit the choice of users so that they don’t choose “Occupation of physiotherapist” when making a “Referral to physiotherapist” because one is an occupation and one is a type of procedure.

5. It allows you to study cohorts…

And finally, the title of the article.

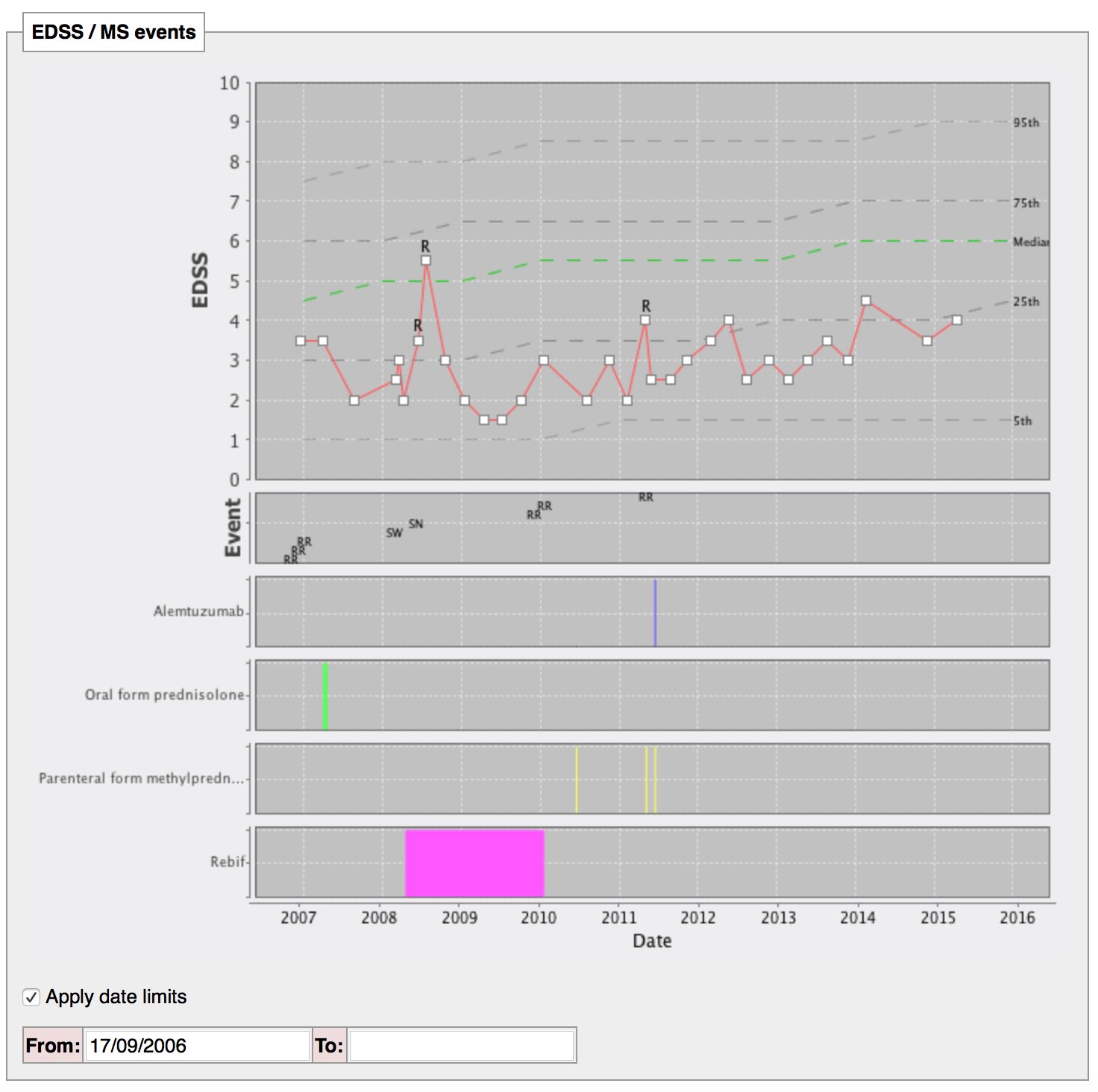

Once you implement SNOMED-CT, you can start to do clever things like, show me how the patient in front of me is doing compared to all of my patients with this disease. You can see this for multiple sclerosis here, but it is possible to do for other disorders as well.

In fact, we can now do the same but sub-stratify to show how you compare to patients with a disease onset at a similar time of life or of the same gender.

Defining cohorts means defining the characteristics of our patients, and SNOMED-CT is the solution. We can then stratify our patient groups according to those characteristics, whether it be their medical diagnoses, the procedures to which they have been through, their treatments current and past or any other characteristic.

How can we make sense of patient reported outcome measures without understanding and stratifying our patients?

Importantly, it doesn’t matter if someone has coded a diagnosis as a highly specific diagnosis as one can map this to a more generic high-level diagnosis and then use that perform aggregated analysis. So for example, if a clinician enters a very specific sub-type of “bronchiolitis”, then it doesn’t matter as we can subsequently aggregate using a higher-level concept and still identify the patient.

Finally, how can we implement algorithmic analysis and artificial intelligence without an understand of these characteristics? Assessment of, for example, deteriorating renal function is critical on knowledge of recent diagnoses and medications given, and structured data is vital in supporting the research required in applying artificial intelligence in healthcare. The routine and systematic collection of SNOMED-CT forms a critical part of the foundation of any programme to implement such systems.