Clinical information system design: 1. The medical record

“You’re a victim of it or a triumph because of it. The human mind simply cannot carry all the information without error so the record becomes part of your practice.”

Dr Larry Weed, Internal Medicine Grand Rounds, 1971

The medical record encompasses and complex, disparate and evolving collection of information relating to the day-to-day care of an individual patient. Aggregated, such data provide valuable information about cohorts of patients managed by a clinical service supporting clinical governance and the management of the that service.

Paper medical records

Paper medical records are expensive, poorly accessible and do not support team working effectively. They are frequently poorly structured and while they contain large amounts of data, it is difficult to use those data to support clinical care. Paper records must be tracked and within a large organisation and such records need to be made available to clinical and administrative staff in order to appropriately manage the patient. This is particularly difficult when a single patient may be under the care of multiple services which is particularly common for patients with chronic long-term health conditions.

Clinical governance

``If you can’t audit a thing for quality, it means you do not have the means to produce quality’’.

Dr Larry Weed, Internal Medicine Grand Rounds, 1971

Clinical governance is a framework in which we are accountable for continuously improving the quality of our services safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care can flourish.

An important part of clinical governance is in the use of data to understand both process and outcomes. A typical clinical department will know how many patients are waiting for an outpatient appointment but will not be able to understand why they are waiting or understand a patient’s eventual outcome because usually only administrative data are collected systematically.

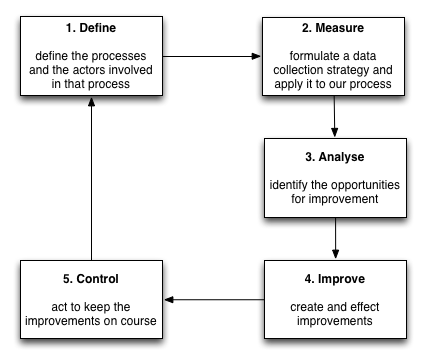

Many clinical teams will undertake service improvement projects or clinical audits, in which a clinician identifies a problem, undertakes to measure that problem by clinical audit, analyses the results and makes an intervention in order to solve that problem. For example, a typical clinical audit might be in the assessment of risk of deep vein thrombosis in inpatients in which a doctor will systematically analyse the paper notes of a group of inpatients, record and present the results and enact a change to improve those results with a plan to re-audit after that intervention. Such a methodology has been formalised by the Six Sigma quality initiative in which five steps form a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement:

Such continuous improvement is possible with paper records, but it cannot be performed systematically and routinely, requires a large amount of manual intervention and the cycle of improvement is slow; the analysis of results and a plan of action to effect improvement may take months with no guarantees that any systematic assessment of those interventions will be performed.

It therefore follows that the routine and systematic collection of process and clinical outcome data offers the potential to radically improve the efficiency of the continuous improvement lifecycle as long as sufficient consideration is given to the use of such data, the context of those data and an understanding of the processes in which those data are involved.

Electronic medical records

Electronic medical records and workflow should model and abstract real-life processes but digitisation of paper processes should not be a slavish exact copy of existing processes, particularly when technology offers opportunities to improve the process of healthcare.

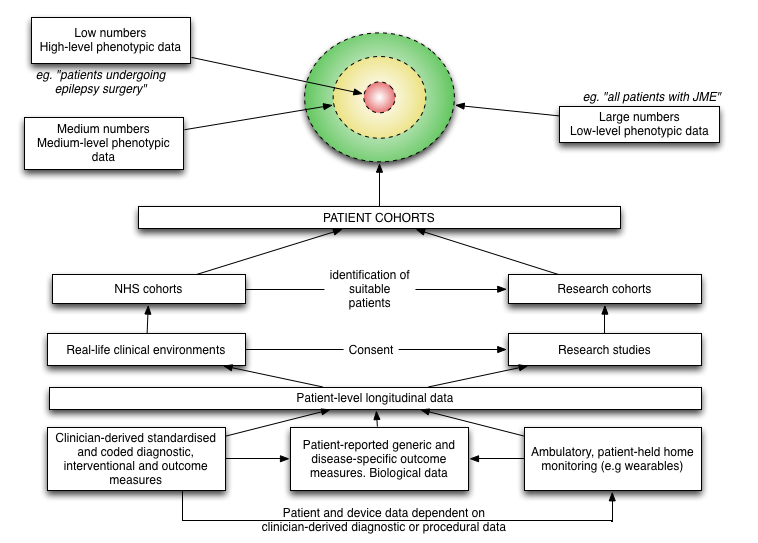

Indeed, we are facing an explosion of clinical data created by health professionals, administrators and patients themselves and clinical information systems must consider how they will integrate and make such data useful in clinical practice. For example, this figure:

shows how all of these sources of data are mutually dependent on one another. For example, what is the point in recording patient reported outcome measures if that data cannot be safely linked to a particular intervention or procedure and the co-morbidities and baseline assessments for that patient?

The logical conclusion is that we will always have a multiplicity of systems and that in order to create robust clinical systems that outlive our current level of technological advancements, we have a responsibility to insist on open well-documented data standards, to integrate a well-developed clinical terminology, and foster collaboration, iterative development and embrace interoperability.